08 December 2016

A handful of books

If I would recommend my favorite reads of the year, I would go for the ones that grow in stature in my mind. Out of the forty-odd books from various genre I read this year, I choose to highlight novels that I feel I have never actually finished reading because they linger still in my memory. Some of these novels I did not instantly "like" or "love" that much during the time I read them, "like" and "love" I find to be terms that are transcended by only a handful of novels. These books challenged my perspective of the world and disrupted my thought processes. In hindsight, I look at my "favorite" reads as resisting the likeability factor. César Aira talks of "retrospective comprehension" as the advantage of literature over other artistic forms. Novels allow readers to form mental pictures from words, and these words had the potential to turn upside down our deeply held assumptions at the start of book because of a carefully withheld detail or fact, the revelation of which at the last page could bring a new level of understanding to what has previously transpired.

Here then are five novels that made my year. They are translated from four languages: Italian, Filipino, Cebuano, and Hiligaynon. The four books translated from Philippine languages are not readily available outside the country – in fact, some of them are even hard to find in my country; one needs to search them out! – so it's like I am offering a reading list of possibilities or potentialities. It's like a list of fictional books from the Invisible Library, nonexistent in many parts of the world and could only live in the imagination of some readers. So here they are: their obscurity could not dim their greatness.

1. Contempt by Alberto Moravia, translated from the Italian by Angus Davidson

My contempt for the main character and his funky first person narration could not dampen my admiration for its brilliant take on the superficiality of modern life weighed down by materialism and political correctness. The unreliable narration was perhaps rivaled only by The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro. (review)

2. Ang Inahan ni Mila (Mila's Mother) by Austregelina Espina-Moore, translated from Cebuano by Hope Sabanpan-Yu

Of the four novels by Espina-Moore that I've read, this one stands out for the comedy and the roundness of its titular character, a domineering mother and wife and a villainous force to reckon with. Mila's mother is a quirky woman whose lot in life may be determined by her past struggles and class prejudices. As the novel progresses, one discovers much else about her character that made her an altogether sympathetic figure. (review)

3. Juanita Cruz by Magdalena Gonzaga Jalandoni, translated from Hiligaynon by Ofelia Ledesma Jalandoni

Another first person novel told in a perfectly calibrated voice of its eponymous narrator, Juanita Cruz is an immersive and transportive novel of adventure of a rich girl escaping her upper class upbringing to become a fully empowered woman.

In my review I take note that Jalandoni, along with Ramon Muzones and many other deserving novelists, was several times bypassed or not even considered for the award of National Artist of Literature. The sad thing is, from a dozen or so already included in the roster of Philippine National Artists, a couple of writers does not have an outstanding body of work to speak of. It is shocking to see how the cultural arbiters failed to honor deserving novelists from other regions and simply could not distinguish the difference between cultural workers and true artists. I wonder what future is in store for the literature of a country whose best writers were not even accorded the full respect and honor due to them. (Pardon the rant, my review post is in here.)

4. Shri-Bishaya by Ramon Muzones, translated from Hiligaynon by Ma. Cecilia Locsin-Nava

My review of this book does not really give full justice to its epic grandeur. I mean, in addition to the foundation myth and love story, I have not even described the superlatively dramatized fight scenes in the book. There is the competition between two warring factions on who would be the first to produce the powerful weapon of lantakas and kirabon. There are supernatural encounters with giant snakes and monsters, well-choreographed maritime battles, and guerrilla warfare on the ground.

This is simply a well-written action fantasy. Its political ramifications, however, are still as relevant as today's news. When the book described repeatedly – too many times for one's comfort – that "sans prior investigation, a person could be thrown into a river full of man-eating crocodiles, pilloried and fed to the ants, hanged on the lunok tree, buried neck-deep in hot sands, cut, quartered, and fed to wild beasts, and subjected to other forms of gruesome tortures", one could be forgiven for glossing over the exaggerations present in a fictional narrative. But once confronted in real life by gruesome allegations involving crocodiles, quartering, dumping, etc., then the reader can only surmise that between allegations in life and in fiction, one or both versions must be true.

If only someone is bold enough to adapt this into a mini-series. Enough of the second-rate, trashy imitation fantasies that are celebrated in TV today. (review)

5. Typewriter Altar by Luna Sicat Cleto, translated from Filipino by Marne L. Kilates

In Typewriter Altar, a middle-aged would-be writer looks back on her childhood and adult life full of domestic baggage and angst. She is also full of unexplained guilt and grief whose magnitudes seemed to exceed those of the fanatic carriers of original sin. The writer's problematic relationship with her father is the central pivot of the story. The episodic story revealed the interior life of a writer struggling with her craft, with demons and ghosts, and with the poetic allure of melancholic existence. (review)

04 December 2016

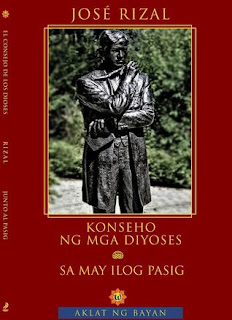

El consejo de los dioses

"El consejo de los dioses" in Konseho ng mga Diyoses; Sa May Ilog Pasig (El Consejo de los Dioses; Junto al Pasig) by José Rizal, translated by Virgilio S. Almario and Michael M. Coroza (Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, 2016) [dual language edition]

On 23 April 1880, the Liceo Artistico Literario de Manila accepted entries for an annual writing contest to commemorate the 264th anniversary of the death of Miguel de Cervantes. For that literary competition the nineteen-year old José Rizal (1861-1986) submitted a one-act play about an unusual literary competition called El consejo de los dioses. In his play, the gods reunited in Olympus to serve as literary jurors and choose from among three writers the most deserving of immortality. The finalists were: Homer, Virgil, and Cervantes. No, this was not a conventional Nobel Prize for Literature. The judging panel could not arrive at a consensus choice from among the three formidable writers. Each writer had his own celestial champion. The heated deliberations of the gods almost resulted to a Ragnarök of sorts. If not for the wise intervention of Jupiter and one impartial judge, the brewing conflict among the judges would have resulted to a civil war among the divine.

The play opened with Jupiter announcing the idea behind the literary contest, the three major prizes to be won by the laureate (a soldier's trumpet, a lyre, and a crown of laurel, all magnificently crafted), plus the criteria and scope of judging. Jupiter's motive behind the contest – commemorating the triumph of the deities against the rebellion of Titans now incarcerated in Tartarus – was similar to the nasty Hunger Games.

JUPITER: Nagkaroon ng isang panahon, mga kataas-taasang diyoses, na ang mga suwail na anak ni Terra ay nagtangkang makaakyat sa Olimpo upang agawin sa akin ang kaharian, sa pamamagitan ng pagpapatong-patong ng mga bundok. At natupad sana ang kanilang nasà, nang walang anumang alinlangan, kung hindi nagtulong ang inyong mga bisig at ang kakila-kilabot kong mga kidlat upang ihulog silá sa Tartaro at ibaón ang iba sa púsod ng naglalagablab na Etna. Ang ganitong kalugod-lugod na pangyayari ay nais kong ipagdiwang nang buong dingal, na siyáng nababagay sa mga inmortal [...] Kayâ nga, ako, ang Kataas-taasan sa mga diyoses, ay nagpapasiyang ang pagdiriwang na ito ay magsimula sa isang timpalak-panitik. Ako'y may isang marangyang trumpeta ng mandirigma, isang lira, at isang koronang lawrel at pawang napakarikit ang pagkakagawa. [...] Ang naturang tatlong bagay ay magkakasinghalaga, at ang makilálang may napakataas na ambag para sa pagkalinang sa panitikan at sa mga katangian ng puso't damdamin ay siyáng magkakamit ng nasabing kahang-hangang hiyas. Ipakilála nga ninyo sa akin na ang mortal na sang-ayon sa inyong paghatol ay karapat-dapat na tumanggap ng mga ito.*

–

JÚPITER.

Hubo un tiempo, excelsos dioses, en que los soberbios hijos de la tierra pretendieron escalar el Olimpo y arrebatarme el imperio, acumulando montes sobre montes, y lo hubieran conseguido, sin duda alguna, si vuestros brazos y mis terribles rayos no los hubieran precipitado al Tártaro, sepultando á los otros en las entrañas de la ardiente Etna. Tan fausto acontecimiento deseo celebrar con la pompa de los inmortales [...] Así, que yo, el Soberano de los dioses, quiero que comience la fiesta con un certamen literario. Tengo una soberbia trompa guerrera, una lira y una corona de laurel esmeradamente fabricadas [...] Las tres valen igualmente, y el que haya cultivado mejor las letras y las virtudes, ese será el dueño de tan magníficas alhajas. Presentadme, pues, vosotros e mortal que juzguéis digno de merecerlas.

One by one, the bookworm-gods spoke and nominated their favorite writer. Juno made a case for Homer on account of his bold and daring ("matapang at pangahas") Iliad and his thoughtful and restrained ("mapaglimi at mapagtimping") Odyssey.

After Juno, Venus took center stage and respectfully objected to the former's choice. She herself made an impassioned plea for Virgil who celebrated the life of her son Aeneas (yes, these gods had their own interest in mind, they were not about to inhibit themselves from the proceedings!). She pointed out to Jupiter the great and merciful quality of Aeneas compared to the fiery temperament of Achilles. For her, Virgil satisfied all the criteria of the singular writer Jupiter was looking for: the one with a substantial contribution to the cultivation of literature and the heart ("may napakataas na ambag para sa pagkalinang sa panitikan at sa mga katangian ng puso't damdamin" / "el que haya cultivado mejor las letras y las virtudes").

A word war ensued between Venus and Juno, after which Minerva took the stage and made an equally heartrending plea for Cervantes, the "son of Spain" who was at first a neglected and pitiful figure (Minerva was alluding to the adventures of Cervantes as a soldier before becoming a novelist) before giving birth to the light his masterpiece.

Ang Quijote, ang kanyang kahanga-hangang anak, ay isang latigong nagpaparusa at nagwawasto ng mga kamalian, nagpapabulwak hindi ng dugo kundi ng halakhak. Isa itong nektar na hinaluan ng mga birtud ng isangmapait na medisina; isang kamay na humahaplos ngunit matigas na pumapatnubay sa mga pasyon ng tao.

–

EL QUIJOTE, su parto grandioso, es el látigo que castiga la risa; es el néctar que encierra las virtudes de la amarga medicina; es la mano halagüeña que guía enérgica á las pasiones humanas.

And then Minerva discussed some more the form of enlightenment Cervantes brought not only to his land but to other shores. Apollo then spoke to second Minerva's appreciation of the Spanish novelist, with this parenthetical quip between his lofty statements: "I implore you not to assume I am partial to Cervantes because he devoted many beautiful pages to me." ("Ipinakikiusap ko sa inyo na huwag ipalagay na ako'y mahilig kay CERVANTES sapagkat ako'y pinag-uukulan ng kanyang maraming magagandang pahina." / "Os ruego no me tachéis de apasionado porque CERVANTES me haya dedicado muchas de sus bellas páginas.")

The deliberation of the gods continued becoming less and less godlike (read: uncivil), with some of them resorting to the oldest tricks in the book: appeal to pity and argumentum ad hominem.

Marte (Mars) joined the fray by slamming Cervantes who apparently defamed him in the novel and ridiculed his exploits ("ang aklat na nagpabagsak sa lup ng aking kaluwalhatian at umuyam sa akong mga nagawa" / "el libro que echa al suelo mi gloria y ridiculiza mis hazañas se alce victorioso"). The angry Marte even marched to the middle of the hall, issued a challenge with his defiant eyes, and brandished his sword.

Minerva spoke again in support of Cervantes and contextualized the Spanish writer's position on the use of arms and letters. (I think she refers to Don Quijote's discourse on arms and letters.) Then she accepted Marte's challenge and prepared for an Olympus showdown. Belona sided with Marte, while Apollo hopped to Minerva's side and stretched out his arrow ready for battle.

Seeing the warlike attitude of the gods, Jupiter's temper flared and he wielded his lightning. Like the wise Solomon he ended the debate by enlisting the help of a most impartial judge who will weigh (literally) the books in her scales using the highest standard possible (not the thickness, one presumes).

Mercurio put each of the two books (the Aeneid and the Quijote) first on the scales of Justice, and what do you know, the scales tipped right in the middle, not a hair's breadth more or less to the right or left! The two tomes were equal in weight. Mercurio removed the Aeneid and replaced it with the Iliad. Up and down went the two scales, up and down, the suspense built up. Then the two scales would stop at the very same level! Justice had spoken not in so many words. What Justice said, was justice served. Jupiter distributed the prizes to the three candidates.

JUPITER: [...] Mga diyoses at mga diyosas: Naniniwala ang KATARUNGAN na magkasimbigat ang tatlo: patas. Magsiyukod kayo, kung gayon at ibigay natin kay HOMERO ang trumpeta, kay VIRGILIO ang lira, at kay CERVANTES ang lawrel. Samantala, ilalathala ng FAMA sa buong daigdig ang pasiya ng KAPALARAN.

–

JÚPITER.

[...]

Dioses y diosas: la JUSTICIA los cree iguales; doblad, pues, la frente, y demos á HOMERO la trompa, á VIRGILIO la lira y á CERVANTES el lauro; mientras que la FAMA publicará por el mundo la sentencia del DESTINO.

Rizal's "Alegoría", as El consejo de los dioses was subtitled, unanimously won the first prize from the Liceo Artistico Literario de Manila. The play's epigraph "Con el recuerdo del pasado entro en el porvenir" (“I enter the future remembering the past”) hinted at the how the young Rizal valued and appreciated literature not only in literary terms but on "the weight of history", a world history fraught with monsters and wars, cruelties and inhumanities.

Unlike his two famous nationalist novels, Rizal's short play was often neglected because he wrote it when he was only a teenager. But here one could detect the source of didacticim in Philippine novel writing where writings were supposed to not only contribute to the development of literature but also to contribute to a positive change in attitudes and behaviors. The only possible arbiter of such writings is justice and to find justice in a work is to weigh them dispassionately and blindly. For Rizal, works that serve justice in all its forms are the kind of works that last, the works that must be celebrated are the ones that celebrate human dignity and human rights. Perhaps it is the "rights-based framework" of literary criticism that integrates the piecemeal concerns of Philippine literature. Not the Marxist alone, not the nationalist, not the feminist, not the queer, not the postcolonial.

*Above quotations in Filipino are from the translation of Virgilio S. Almario. The Spanish quotations are taken from El consejo de los dioses at Project Gutenberg which has slight variations from the Spanish in the book published by the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino.

02 December 2016

All books 2016

I read 42 books this year, lower than last year, which is lower than the year before that. This is the lowest since I started counting (and blogging) in 2009. The peak year is 2012 when I read 84 books.

Goodreads tells me I read 733 books in my lifetime so far, but this number is conservative. I could not account for all titles I read prior to 2009. I did not include in the catalog the books I read from the Hardy Boys series, Nancy Drew series, Hardy Boys Casefiles series, and Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys Supermystery series. Not to mention the Bobbsey Twins series and Tom Swift series. Not counting the children's picture books I pored over in the library. Funny graphic comics and other local comics being rented out by my grandmother in her sari-sari store. I am getting nostalgic.

Time is very forbidding, but I am happy to list whatever books I have the chance to read.

1. Contempt [post 1, post 2] by Alberto Moravia, tr. Angus Davidson

2. The Character of Rain [related post] by Amélie Nothomb, tr. Timothy Bent

3. Dr. Jekyll at G. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, tr. Largo Labor

4. Pitóng Gulod pa ang Layo at Iba pang Kuwento (Seven Hills Away and Other Stories) by N.V.M. Gonzalez, tr. Ed Maranan

5. The Golden Dagger by Antonio G. Sempio, tr. Soledad S. Reyes

6. Hinggil sa Konsepto ng Kasaysayan (On the Concept of History) by Walter Benjamin, tr. Ramon Guillermo

7. Bulosan: An Introduction With Selections by E. San Juan Jr.

8. Ang Maglaho sa Mundo: Mga Pilíng Tula (To Vanish from the Face of the Earth) by Jorge Luis Borges, tr. Kristian Sendon Cordero.

Also read and reviewed: Shakespeare's Memory, from Collected Fictions by Jorge Luis Borges, tr. Andrew Hurley

9. Bibliography of Filipino Novels: 1901-2000 by Patricia May B. Jurilla

10. Haring Lear by William Shakespeare, tr. and adapt. Nicolas B. Pichay

11. Konseho ng mga Diyoses Sa May Ilog Pasig (Council of the Gods by the Pasig River) by José Rizal, tr. Virgilio S. Almario and Michael M. Coroza

12. The Monkey and the Tortoise: A Tagalog Tale by José Rizal, illus. Bryan Anthony Paraiso

13. The Bamboo Stalk by Saud Alsanousi, tr. Jonathan Wright

14. Shri-Bishaya [post 1, post 2] by Ramon Muzones, tr. Ma. Cecilia Locsin-Nava

15. Juanita Cruz by Magdalena Gonzaga Jalandoni, tr. Ofelia Ledesma Jalandoni

16. A Lion in the House by Lina Espina-Moore

17. Typewriter Altar by Luna Sicat Cleto, tr. Marne L. Kilates

18. A Place in the Country by W. G. Sebald, tr. Jo Catling

19. Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change by Elizabeth Kolbert

20. Halina Filipina by Arnold Arre

21. House of Cards by Austregelina Espina-Moore, tr. Hope Sabanpan-Yu

22. Diin May Punoan sa Arbol (Where a Fire Tree Grows) by Austregelina Espina-Moore, tr. Hope Sabanpan-Yu

23. Ang Inahan ni Mila (Mila's Mother) by Austregelina Espina-Moore, tr. Hope Sabanpan-Yu

24. Martial Law Babies by Arnold Arre

25. Zsazsa Zaturnnah sa Kalakhang Maynila (Part Two) by Carlo Vergara

26. Love in the Rice Fields and Other Short Stories by Macario Pineda, tr. Soledad S. Reyes

27. Pag-aabang sa Kundiman: Isang Tulambúhay (Waiting Along Kundiman: Autopoetry) by Edgar Calabia Samar

28. At the Same Time: Essays and Speeches by Susan Sontag, ed. Paolo Dilonardo and Anne Jump

29. 84, Charing Cross Road by Helene Hanff

30. Ilustrado by Miguel Syjuco

31. Testment and Other Stories by Katrina Tuvera

32. A Blade of Fern by Edith L. Tiempo

33. At the Mind's Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor of Auschwitz and Its Realities by Jean Améry, tr. Sidney Rosenfeld and Stella P. Rosenfeld

34. Encyclical on Climate Change and Inequality: On Care for Our Common Home by Pope Francis

35. The Metamorphosis, In the Penal Colony, and Other Stories by Franz Kafka, tr. Joachim Neugroschel

36. A Roomful of Machines by Kristine Ong Muslim

37. The Pact of Biyak-na-Bato and Ninay by Pedro A. Paterno, tr. National Historical Institute and E. F. du Fresne

38. The Birthing of Hannibal Valdez by Alfrredo Navarro Salanga, with an accompanying Pilipino translation by Romulo A. Sandoval

39. The Alien Corn by Edith L. Tiempo

40. Stringing the Past: An archaeological understanding of early Southeast Asian glass bead trade by Jun G. Cayron

41. The True Deceiver by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal

42. Ang Balabal ng Diyos / Ang Silid ng Makasalanan (The Cloak of God / The Sinner's Room) by Rosario de Guzman Lingat [review of the English translation The Cloak of God here]

20 November 2016

To be modern: On Contempt (2)

Contempt by Alberto Moravia, tr. Angus Davidson (New York Review Books, 2004)

Riccardo Molteni decided to write down his memories of his wife and their doomed love affair in order that she would be exorcised of him. So he dwelt in his own melancholic recollections, seemingly sustained by a framework of pathological grief, romanticism, and naivete. He could even be considered heroic in his self-imposed funk, preferring to dream of a world in which he felt he was for ever barred, "a world in which people loved without misunderstandings and were loved in return and lived peaceful lives." All this inner emotional acrobatics of Riccardo only served to implicate him in the mess of a narrative bathed in pathos and dreams. The gaps in his memory he could only attribute to "a fainting fit, or ... some kind of collapse or unconsciousness very like a fainting fit."

Contempt represented a kind of trap for readers. The consistency of tone throughout the narrative reinforced an impermeable, blameless quality to the way it was told. Ultimately it proposed certain ideas about the perception of classical art and how it was valued by the present world through interpretations and endless interpretations. The varied interpretation of the Odyssey inside Contempt was a sneaky device. It brought to light the variety of meanings that could be derived from the intersection of the classic and the modern. Specifically, how the Odyssey was interpreted by the characters yielded many openings into the story. The variety of views into the epic poem, and its correspondences with the marriage plot, became the launching pad for dichotomizing modernity and tradition, contemporary and classicism, civilization and savagery. Must we interpret the classics in our own time using our own zeitgeist or should we stick to the classical framework of Ulysses' heroism and nobility? Must the modern (and its attendant philosophical and psychological baggage) intrude so much on the sacrosanct value of the epic?

Riccardo wanted for his screenplay a version of the Odyssey that hewed closely to the supposed original intents of Homer ("made as Homer wrote it"). Rheingold, the movie director hired by Battista the producer, wanted a modern adaptation of it, with a Freudian spin on the relationship between Ulysses and Penelope ("in accordance with the latest discoveries in modern psychology"). The distance of time, the wide gulf between the ages, was very pronounced in this. "Dante is Dante: a man of the Middle Ages," said Rheingold. "You, Molteni, are a modern man." Ostensibly about the breakdown of a marriage, the novel could also be about the interpretation and reinterpretation of art through the ages. We were no longer just reading about one failing marriage but the contextual, literary clues behind it. The characters were now dishing out concepts like heroism and steadfastness, being civilized and being barbaric.

Was Emilia breaking off with Riccardo because he was "civilized", as Rheingold described him? If by "civilized" we mean not stepping on other toes, being politically correct, guided in life mainly by the invisible hand of materialism, prodded on by the selfish gene, then Riccardo must be it. He had a certain deficiency in his character, a certain insensitivity. He must be one of the most insensitive characters in fiction, rivaled to some extent by the intellectual coldness and rationality of Shimamura in Yasunari Kawabata's Snow Country.

In Emilia's traditional view of the world, at least as Riccardo interpreted her, "civilized" alone would not cut it. Civilized might be the working of a pure intellect or reason. It is not empathy; one has to care sincerely, genuinely. Though not the literary type, Emilia was perhaps the better interpreter of feelings. Her actions spoke volumes—not in so many words as the wordy Riccardo spouted in his funk-filled memoir—about rejecting the imbalance in her husband's temperament, the "lack" that made him superfluous and less than a man.

Whether I was despicable or not—and I was convinced that I was not—I still retained my intelligence, a quality which even Emilia recognized in me and which was my whole pride and justification. I was bound to think, whatever the object of my thought may be; it was my duty to exercise my intelligence fearlessly in the presence of any kind of mystery.

By Riccardo's own admission, only his intellect could sustain him. Without it he would not be able to fully crystallize his thoughts and conjure the whole story. Emilia, for her part, would be sustained by the powerful feeling of contempt for him. Given the masculine forces vying for her attention, contempt could only be her handhold.

The modern novel, Borges believed, was a narrative devoid of heroes and knights and epic battles. It was filled with superfluous characters bound to degrade themselves by their own telling and bound only to demonstrate their epic psychological breakdown. Modernization was, necessarily, and according to Riccardo, a work "of debasement, of degradation, of profanation", which was how he described James Joyce's Ulysses, an adaptation with which Borges also had several issues.

The modern novel is the novel of literary criticism. How art is or ought to be perceived is already contained in it. Because it is already aware that it is a narrative construction (because its building block is complex memory), its artfulness is detected in this self-awareness. Modernism in novels like Moravia's, realist or otherwise, is already colored by interpretation, by mimicking and then flouting the conventions of literary criticism.

And so the characters in these novels would be intellectual and literary. They would not be typecast as hero or villain, and they would not be tied down by any labels. They would not commit to one neat explanation of their profound or banal situation. Instead they would go on, even after the last page; they would not cease to be the hero-character or the villain-character, to be Ulysses or to be Penelope. They would continue to speak and spin meanings and assert their unfathomable modernness. And the novelist would not allow any of these characters to have the last word.

The contribution of modern novels, imho, was proffering challenge to envision the alternative pathways, many views and perspectives, often the very opposite views of the popular and the commonplace, in fact. And to acknowledge that barbarity plays a role in exploring generous and compassionate ways of transacting with fellow human beings. If by "barbarity" we mean disabusing oneself of the ideal notion of politics, being pragmatic but not ruthless and unfeeling, accounting for savagery and pure appetite (the Battistas of the world), and sometimes wallowing in a funky tedium and emerging with a certainty that everything, the world, was not tidy and will never be.

Rheingold resumed: "And now I should like to explain some of my ideas to you. I presume you can drive and listen at the same time?"

"Of course," I said; but at that same moment, as I turned very slightly towards him, a cart drawn by two oxen appeared out of a side road and I had to swerve suddenly. The car heeled over, zig-zagged violently, and I had considerable difficulty in righting it, just in time to avoid a tree, by a narrow margin. Rheingold started to laugh. "One would say not," he remarked.

"Don't bother about that," I said, rather annoyed. "It was quite impossible for me to have seen those oxen. Go on: I'm listening."

In simple words, modernity was openness to ideas, driving and listening at the same time, trying to avoid freak accidents, trumping a calcified vision of a new world order. Bring in the daring adaptations. The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood. Gertrude and Claudius by John Updike. Bring in literary criticism inside novels. Die Ästhetik des Widerstands by Peter Weiss. Perhaps years from now, someone would write or adapt in post-modern fashion a novel in which characters debate about the motivations of the characters in Contempt.

13 November 2016

The task of the translator

In The Character of Rain, translated by Timothy Bent, Belgian novelist Amélie Nothomb had a gifted toddler-age girl already speaking and reading very well in French and Japanese. These talents she intentionally concealed from her family except her nanny, the only one she had had regular conversations with.

"Do you really understand everything I'm saying to you?"

"Yes."

"You learned how to speak Japanese before you learned to speak French?"

"They're the same thing."

And indeed, I hadn't known there were such things as separate languages, only that there was one great big language and that one could choose either the Japanese version of it or the French version, whichever you preferred. I had not yet heard a language I couldn't understand."

The child was given to understand that that there was only one vocabulary from which she could pick out words in French or Japanese. This was a child who taught herself to read just by flipping books. If there was another language she could learn, then she likely would just expand the vocabulary of her single, perfect language.

In a post-Babel, multicultural world, this belief in a single, coherent language was a perfect dream and a child's wish. This belief in a unifying language was evident in the process and function of translation to combine together languages into a perfect harmony. Walter Benjamin thought so in "The Task of the Translator", his famous and widely anthologized essay that was a staple crop in translation studies:

Kayâ nga ang layon ng pagsasalin, sa madalîng salitâ, ay ang pagpapahayag ng pinakamatatalik na ugnayan o relasyon ng mga wika. Hindi maibubunyag o maipakikita ng mismong pagsasalin ang matatalik na relasyong ito; gayunman, maaari nitóng katawanin o bigyang-representasyon ang mga nasabing relasyon kung isasakatuparan sa paraang panimula at intensibo.... Gayunman, ang ipinalalagay na matalik na ugnayang ito ng mga wika ay isang relasyon ng di-pangkaraniwang pagtatagpo. Nakasalig ito sa katotohanang hindi magkakahidwa ang mga wika sa isa't isa, at gaya ng tanggap na paniniwala at taliwas sa lahat ng mga ugnayang pangkasaysayan, may pagkakaugnay-ugnay ang mga wika sa kanilang ibig sabihin. [1]

[Translation thus ultimately serves the purpose of expressing the innermost relationship of languages to our answer. It cannot possibly reveal or establish this hidden relationship itself; but it can represent it by realizing it in embryonic or intensive form.... As for the posited innermost kinship of languages, it is marked by a peculiar convergence. This special kinship holds because languages are not strangers to one another, but are, a priori and apart from all historical relationships, interrelated in what they want to express.]

If Benjamin was to be believed, then translation was the ideal, harmonizing medium to filter and express linguistic meanings and effect. The attempt to transfer what was written from one language to another was an attempt to reconcile discrepant thoughts and philosophy, thereby bringing languages closer (in innermost kinship) together. Ideas in one language might be resistant to translation. Put under the legislating mind of a capable translator, these ideas would be carefully considered and transformed and coded in another language. There was an aura of mystery to this transformation, the transformed idea authenticated or validated by how much it retained or emitted the energizing effect, the echo or reverberation (alingawngaw), of the original.

In another section of his essay, Benjamin asserted that translations were capable of hiding the language of truth.

Ano't anuman, kung may isang wika ng katotohanan na panatag at tahimik na kinalalagakan ng pinakamahahalagang lihim na pinagsisikapang matuklas ng lahat ng pagdalumat, ang wikang ito ng katotohanan, kung gayon, ang tunay na wika. At ang wikang ito—na ang lahat ng pagpapalagay at paglalarawan ay inaasahang makamit ng pilosopo—ay masinsinang nakakubli sa salin. [1]

[If there is such a thing as a language of truth, a tensionless and even silent depository of the ultimate secrets for which all thought strives, then this language of truth is—the true language. And this very language, in whose divination and description lies the only perfection for which a philosopher can hope, is concealed in concentrated fashion in translations.]

Benjamin was obviously talking of good translations wherein the true language hides. In his essay, he took great pains to characterize the "unrestrained license of bad translators" [2] who were mainly concerned with the transfer of "inessential content" (di mahalagang nilalaman) and suffering from literalness. Literalness was not entirely evil in design. In fact, Benjamin understood that the desire to be faithful to form (yet another way of being literal) impedes the transfer of meaning. Translation as a balancing act meant a text's fidelity (literalness) to form was considered alongside freedom to diverge from form and content.

But negative formulation to define bad translations could only get one so far. It was only Benjamin's entry toward exploring the issues of translatability, liberation of meaning, and the hidden poetry in languages.

Unity and truth in language (through the translation medium) were concepts leading toward the dream for another language. Here we were given an optical image of translation as facilitating the view of the original through transparent lenses.

Ang pinakamataas na papuring masasabi, lalo na sa panahon ng pagkakaakda ng salin, ay hindi ang "nababása ang salin na para bang orihinal ito sa wikang pinagsalinan." Kataliwas nitó, ang halaga ng katapatan na sineseguro ng literal na salin ay nása pangyayaring sinasalamin ng akda ang marubdob na lunggating maging ganap (kompleto) ang wika. Lagusang-tanaw (transparente) ang tunay na salin: hindi pinalalabo ang orihinal, hindi tinatabingan ang liwanag ng orihinal, at sa halip, hinahayaang makapaglagos ang wikang wagas—na animo pinag-ibayong lakas ng sarili nitóng anyo—upang lubos pang masinagan ang orihinal. Nagagawang posible ito sa pamamagitan ng pagtatawid ng sintaksis nang salitâ-sa-salitâ; at ipinakikita nitó na ang salitâ, hindi ang pangungusap, ang orihinal na elemento ng salin. Sapagkat ang pangungusap ang siyang pader sa harap ng wika ng orihinal, ang salitâ-sa-salitâng paglilipat ang siya namang lagusan.

[It is not the highest praise of a translation, particularly in the age of its origin, to say that it reads as if it had originally been written in that language. Rather, the significance of fidelity as ensured by literalness is that the work reflects the great longing for linguistic complementation. A real translation is transparent; it does not cover the original, does not block its light, but allows the pure language, as though reinforced by its own medium, to shine upon the original all the more fully. This may be achieved, above all, by a literal rendering of the syntax which proves words rather than sentences to be the primary element of the translator. For if the sentence is the wall before the language of the original, literalness is the arcade.]

It was translation that had the capacity to recall pure language, to build the wordy edifice of an expansive novel, sustained and animated by the power of the original novel, with a renewed and renewable force of imagination. The transparent prose of that great novel was the "arcade" or bridge that conveyed stuff both familiar and mysterious, recognizable and strange.

A language of unity, truth, and purity was a language against intolerance, wars, colonialism, racism, and tyranny. Linguistic translation as a liberating force against misunderstanding: this, for Benjamin, ought to be the translator's duty: Ang palayain sa kaniyang sariling wika ang wikang wagas na naengkanto sa banyagang wika, ang palayain ang wikang napiit sa akda sa pamamagitan ng muling pagsulat dito. (To release in his own language that pure language which is exiled among alien tongues, to liberate the language imprisoned in a work in his re-creation of that work.) [3]. Pierre Menard was turning in his grave.

Notes:

1. Quoted from "Ang Tungkulin ng Tagasalin" (The Task of the Translator) by Walter Benjamin, translated into Filipino by Michael M. Coroza, in Introduksiyon sa Pagsasalin: Mga Panimulang Babásahín Hinggil sa Teorya at Praktika ng Pagsasalin, edited by Virgilio S. Almario (Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, 2015). All subsequent quotations in Filipino were from this source.

Coroza based his Filipino version of the essay on three translations: two in English (by Steven Rendall and Harry Zohn) and one in Spanish. All passages in English translations were from Zohn's translation of the essay, in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 1, 1913-1926, edited by Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings.

2. In Coroza's Filipino version: walang habas na kalayaan (loosely: untethered freedom).

3. A literal rendition of the Filipino can be: "To liberate in his own language that pure language which was enchanted within the foreign language, to liberate the language incarcerated inside a work through rewriting of that work."

12 November 2016

On Contempt

Contempt by Alberto Moravia, tr. Angus Davidson (New York Review Books, 2004)

|

| WRAPPED FIGURE, MAKATI CITY, 2016 |

As I came into the sitting-room I saw Emilia sitting in an armchair, her legs crossed, and Battista standing in one corner in front of a bar on wheels. Battista greeted me gaily: Emilia, on the other hand, asked me, in a plaintive, almost melting tone, where I had been all that time. I answered lightly that I had had an accident, realizing at the same time that I was adopting a tone of evasiveness, as if I had something to conceal: in reality it was simply the tone of one who attributes no importance to what he is saying.

By his own direct (or indirect) and conscious (or unconscious) admission, the narrator of Alberto Moravia's frustrating novel was unreliable. He did, and did not, ascribe truth to what he was saying. In fact he said a lot, and what he said betrayed all his surface feelings, so truthful and sensitively conveyed his whining was almost comical and pitiful. Perhaps it was half-meant to be a comedy, half-meant to be a tragedy.

Riccardo Molteni was the unfaithful narrator, and Contempt was the story of his realization of his wife's contempt of him. Emilia fell out of love for him, gradually and suddenly. She came to detest him. Our puzzled narrator was slowly coming to grips with this reality unfolding in front of him without his full participation at first because of his seeming apathy or lethargy or self-delusion. He would easily come across as a buffoon were it not for the perfectly controlled voice held in suspension, telling of his wife's conjugal disaffection in a roundabout way.

Molteni's profession was on point. He was a movie scriptwriter, and so his dramatic situation needed to be told with a bit of suspense, with a bit of flair, an emphatic withdrawal at first of the full blast of meaning before a marital bomb explodes on his face.

And now, as if my eyes had been at last opened to a fact which was clear and yet, till that moment, invisible, I was conscious that this communion might no longer exist between us, in fact, no longer did exist. And I, like a person who suddenly realizes he is hanging over an abyss, felt a kind of painful nausea at the thought that our intimacy had turned, for no reason at all, into estrangement, absence, separation.

Our character was helpless on the page: half-dreaming, half-awake, and clueless. To be fair, the initial symptoms of a wife's love lost were not entirely lost on him. He was not completely surprised when his wife finally broke up with him.

What anchored his endless complaints on the page was the fervor of his folly combined with an intellectualized denial of an intellectualized love. His blind adherence to the romantic notion of constancy was meant to be shattered and witnessed in its full, pathetic glory. The reader was a hapless participant in the awkward affair, forced to observe a private struggle against mechanical passions and manipulated emotions.

The labor and capital of the filmmaking business were hardly to blame, but they sure played a part in the dissolution of his marriage. The writer was enslaved to write something commercial so he could earn a lot of money to pay for his finances. In the process, he neglected the essential connections in his life, which likely contributed to Emilia's estrangement with him.

Working together on a script means living together from morning to night, it means the marriage and fusion of one's own intelligence, one's own sensibility, one's own spirit, with those of other collaborators; it means, in short, the creation, during the two or three months that the work lasts, of a fictitious, artificial intimacy whose only purpose is the making of the film, thereby, in a last analysis (as I have already mentioned) the making of money.

Sacrifices had to be made at the altar of the silver screen. Molteni was practical enough not to be entirely dazzled by the trappings of commercial work, and he knew that to be consumed by "the prospect of the cash" and by the routine and repetition of commercial storytelling could constitute a failure of the imagination: "and indeed the mechanical, stereo-typed way in which scripts are fabricated strongly resembles a kind of rape of the intelligence".

Moravia was a connoisseur of narrative suspension: of suspenseful deferment of confrontations, of manufactured escape from reality. Molteni thrived on self-deception, always on the brink of a deferred insight or revelation in order to deny the bitter pill of truth. But once his marriage plot unraveled, and his life turned upside down, we could be sure he had an apt metaphor, something violent, to bring to his condition.

I was, in fact, convinced now that Emilia could no longer love me; but I did not know either why or how this had come about; and in order to be entirely persuaded of it I must have an explanation with her, I must seek out and examine, I must plunge the thin, ruthless blade of investigation into the wound which, hitherto, I had exerted myself to ignore.

He certainly could bring out the dramatic push he needed to investigate (or rather dissect) the plot of his marriage. All the philosophical noise and intellectualized discourse only served to heighten his odyssey into a cog in the wheel of cash economy.

I was still half-way through the novel and still could not decide whether I need to find out what happened during the island interlude in Capri and whether Molteni's further spiraling out of control is worth all the drama behind it. The reader could not be blamed for being ambivalent towards a forgetful narrator intent on overanalyzing his version of a kollosal divorce. The screenwriter was shrewdly setting up a scene where all lost hopes converge and the light of his life fades to black. Awakening readerly Schadenfreude: maybe it was his writerly strategy to elicit sympathy for belaboring the point of missed connections, missed signals, and conjugal distrust.

31 October 2016

The Golden Dagger

The Golden Dagger by Antonio G. Sempio, translated from Tagalog by Soledad S. Reyes (De La Salle University Publishing House, 2016)

In her Bibliography of Filipino Novels: 1901-2000 (2010), Patricia May B. Jurilla noted that the most prolific novelist in Tagalog was Antonio G. Sempio (1891-1943) for having the most number of published novels in book form. Most novels in Tagalog/Filipino were first serialized in magazines or newspapers before being published in book form.

Between 1917 and 1942, Sempio produced 19 novels, including a translation. According to Jurilla, it was likely that most of these novels were self-published owing to the fact that Sempio was known for peddling his books as he traveled from town to town.

One such novel—Ang Punyal na Ginto (Nobelang Tagalog) (1933)—recently appeared in English translation by Soledad S. Reyes as The Golden Dagger. This novel was notable for being the basis of the first ever "talking" film in the country. In a way, this was the story which finally broke the "silence" of the silver screen.

According to Jessie B. Garcia in A Movie Album Quizbook (2005), cited by Video 48 blog (link), the exhibition of Punyal na Ginto the movie at the Lyric Theater on the Escolta "was made possible with the importation of American technicians and sound camera equipment by two American businessmen and promoters, George F. Harris and Stewart “Eddie” Tait of the Tait Shows carnival fame."

|

| (IMAGE SOURCE: IMDb) |

The plot of The Golden Dagger was a melodramatic and rather tragic treatment of the love between the poor girl Dalisay and the filthy rich boy Dante, with the boy's father, the despotic Don Sergio, doing everything in his power to thwart the affair. In the translator's introduction, Reyes cautioned the reader to look at the novel "against a specific sociopolitical context and an evolving literary tradition", for the reader to "retrieve the novel's original meaning on its own terms". Without the context to situate the novel in the American colonial period fraught with inequalities between the landed rich and the working poor, the novel would be easily dismissed as poverty porn.

The names of the characters were rich in meaning. Dalisay is the Tagalog word for pure and untarnished, and it was her destiny to erase the stain that marked her ill-fated association with Don Sergio and his son. Dante Villa Centeno was the only major character given a full name in the story. It was as if only the rich were the only ones entitled to a full name. Elias, Dalisay's cousin and the third corner of the love triangle, seemed to echo the noble character of Elias in Rizal's Noli Me Tangere. By the end of the book, Elias became like Simoun the jeweler in El Filibusterismo by being rich himself, and like Isagani by derailing Dalisay's plan of revenge. Elias then had the nobility of his namesake, the wealth of Simoun, and the righteousness of Isagani.

The tragic conclusion of the story was foretold in the beginning. What was left to ponder in the novel? The sentimental drama and the momentous, heart-stopping twists and turns; the Philippine sociopolitical background that informed such a story; the ingenious use of the reference code; the narrator's frequent intrusions, his ironic commentaries to the story, and his constant taunting of the reader at the end of the chapters; the verbal and psychological battle of wills between the rich boy and his father, and between the poor girl and the rich boy's father; time lapse and transformations of character. Somehow, too, the corrupt stench of patronage politics and partisanship of the 1930s pre-Commonwealth period still assaulted the nose of the present.

—Oh, no! I'm here to pay you a visit. I'd like to find out what you need and what you think. What can I do for you, friends?

—Ah, if that's what you want to know, there's a whole list—Mang Bastian replied. —First of all, there is only one artesian well that the democrats built at one end of the village nearest the street where their party mates lived; this is not enough. Secondly, the number of students is growing, but since the only public school is small, the students are forced to stop schooling because the school in the town proper is inaccessible.

—But what are your mayor, representative, and senator doing? Why don't you ask them for help?

—Naku! Those officials say they have the people's welfare in mind, that is, when campaigning, but the moment they are elected, they conveniently forget their promises!

—Let me handle this and I'll look into these needs and follow up on them until they reach the office of the Governor-General. We're friends, and I promise to facilitate what your elected officials fail to deliver! [...] But of course they will not dare disappoint me! Do you think the amount of money I donate to their campaigns during election is a pittance? They all entwine themselves around me! Start with Quezon, to the oldest senator, and the representatives, and you may add the secretaries of the various departments. Not one of them can afford to turn me down! They owe me a great deal, and they will not have the nerve to refuse me! Ah! Even the Governor-General has not failed me, not even once!

The proud speaker was Don Sergio, and his certainty of victory spelled the doom not only for the political trajectory of the country but for Dalisay's unwinnable love for Dante.

Don Sergio's "golden dagger" (a transparent metaphor for the unlimited power and resources available to the rich) was poised and ready to fight against Dalisay and her love for Dante. The golden dagger was designed for the systematic terrorizing and breaking down of poor folk who dare cross the path of the ruthless rich.

How would he make the young woman [Dalisay] withdraw her promise? How, ah, how? What if he offered untold riches? He was willing to pay her off since Dante's money was the sole motive driving both mother and daughter [Dalisay and her mother]. He would offer thousands of pesos, or however much it would take, to free his son's ensnared heart. Once she agreed, then there was no more need to talk. Just allow Dalisay to name her price, and he would pay her with alacrity, with a smug smile on his face. But if Dalisay remained firm despite her gentle pleading, he would unleash the terror—he would berate her, threaten her, and put the fear of the Lord in her. If she did not succumb to his entreaties, then he would resort to violence. Nobody who defied him was spared his deadly revenge. This scheme, this one plot was the only alternative that would probably lead to satisfactory results!

The rich were results-oriented, once they put into motion their best-laid plans. Using Plans A to C and other cruel contingencies, their quarry would not be able to escape.

After another round of furious exchange, the police van finally arrived. How could they afford to ignore the master's order? The chief of police was a friend of Don Sergio's, and sending a van over with alacrity was the least he could do.

With the whole political establishment at his side—the so-called "duty-bearers": legislators, judges and lawyers, the police force, the Governor-General!—it was no wonder that Don Sergio would not have the least trouble perpetrating his evil design on Dalisay. The "rights-holder"—the poor, the marginalized, the disenfranchised—would be easily robbed of their rights and freedoms. For her part, Dalisay—even before Miss Saigon—would be forced to perform the ultimate sacrifice. And even if it killed her trying, she would have her revenge, one way or another.

The Golden Dagger was one of the last publications of the De La Salle University (DLSU) Publishing House. According to a major online local bookseller I talked to, the press was no longer in operation. This was a tragedy, not least because the DLSU university press was one of a handful of progressive publishers of translated novels in the Philippines. In 2013, the press released, also in translation by Soledad S. Reyes, two remarkable novels by Rosario de Guzman Lingat.

I am not sure if the movie adaptation is still extant. If it is, I hope I will have the chance to watch this first ever Tagalog movie recorded with sound.

Notes on Bibliography of Filipino Novels: 1901-2000

Bibliography of Filipino Novels: 1901-2000 by Patricia May B. Jurilla (The University of the Philippines Press, 2010)

Patricia May B. Jurilla does a great service to readers and students of Philippine novel in her well researched Bibliography of Filipino Novels: 1901-2000, published by the University of the Philippines Press in 2010. She collated a century's worth of Philippine novel writing and production in three separate lists: (i) English language novels, (ii) Tagalog (Filipino) language novels, and (iii) translations of foreign novels into Tagalog (Filipino) language.

She excluded novels written during the Spanish period (pre-20th century novels) and books with less than 49 pages, the UNESCO standard definition of a book. According to her, she omitted "quite a number of early Tagalog novels" because of this page constraint, with these books "looking more like booklets, chapbooks, or pamphlets really—almost resembling novenas." The page constraint was not followed strictly though as I noticed a book with 48 pages included in the list.

The 1910s was considered the Golden Age of the Tagalog novel, the decade that produced a total of 93 Tagalog titles. Her introduction to the bibliography discussed significant trends and factors that contributed to the production of novels in the Philippines.

After the Americans introduced English language in the country in 1900, it took 21 years before a first novel in the language appeared: A Child of Sorrow by Zoilo M. Galang, which he self-published and later translated into Tagalog as Anak ng Dalita (1960). Self-publication was a common practice during the first half of the century.

According to Jurilla, novels in English generally did not cater to popular taste. Compared to Tagalog novel reading, the Philippine novel in English appealed only to a small readership: those in the upper-middle and upper classes who had command of the English language and who had access to education.

The most prolific Filipino novelist in English was F. Sionil José (10 titles during the period covered), followed by Linda Ty-Casper (9 titles). The most common words included in the titles of novels in Filipino and in Filipino translation were: pag-ibig (love), buhay (life), puso (heart), luha (tears), and bulaklak (flower).

Unfortunately, translations of novels from a Philippine language into English were excluded from the list. Based on my limited search, only two titles appeared in English translation in the period covered by the bibliography—(i) The Lady in the Market by Magdalena G. Jalandoni in 1976; and (ii) Margosatubig: The Story of Salagunting by Ramon L. Muzones in 1979. Both titles were translated by Edward D. Defensor from Hiligaynon language, and both were published by University of the Philippines in the Visayas (Iloilo).

The two books of Don Quixote appeared in Tagalog translation by four translators in 1940. However, according to Virgilio S. Almario, in "Sulyap sa Kasaysayan ng Pagsasalin sa Filipinas" (A Glimpse into the History of Translation in Filipinas), one of the essays in Introduksiyon sa Pagsasalin: Mga Panimulang Babásahín Hinggil sa Teorya at Praktika ng Pagsasalin (Introduction to Translation: Introductory Readings on the Theory and Practice of Translation) (2015), these books were translated based on the English translation.

The only book that appeared in bilingual translation was The Birthing of Hannibal Valdez (1984), originally in English by Alfrredo Navarro Salanga, with an accompanying "Pilipino" translation by Romulo A. Sandoval. I read this book—the author calls it a "novella"—earlier this year.

Needless to say, the bibliography needs to be updated to cover new novels published in the new century. It also needs to be expanded to cover novel output from other vernacular languages with novel tradition such as Hiligaynon, Cebuano, Kapampangan, etc. Several Tagalog (Filipino) titles in the list already appeared in English translation only in the last decade. Annotations on reprinted books need to be updated (e.g., Surveyors of the Liguasan Marsh (1991) by Antonio Enriquez was published under a new title, Green Sanctuary, in 2003; Eric Gamalinda's Empire of Memory (1992) recently appeared in a new edition).

Certain lacunae in the entries needed to be filled (e.g., Carlos Bulosan's novel America Is in the Heart: A Personal Journey was undated. Jurilla made a conjecture that this was likely published in the country in the 1970s. According to Bienvenido Lumbera, in a foreword to Bulosan: An Introduction With Selections, edited by E. San Juan Jr., the Philippine edition was published in 1980.) Perhaps an "online edition" of the lists can serve to validate or update the bibliographical entries.

Although the bibliographer did not mention it, war, disasters, and tragedies were not kind to the preservation of Philippine books and manuscripts. The destruction and looting of libraries during the Battle of Manila in 1945 consigned a lot of the collections to the dustbin.

Jurilla's book is quite handy for anybody interested in reading Filipino novels or, for that matter, investigating novel production and output in colonial, post-war, and post-colonial settings, and pre- and post-martial law regime.

From the list, I only read a measly 7 out of the 365 titles in Tagalog (Filipino), none from the titles in Tagalog (Filipino) translation, and 20 out of 177 novels in English.

This bibliography has already given me an idea on which novels to read next.

A Lion in the House

I don't like to write in books with ink. Books heavily underlined and annotated scandalize me. The blank pages and margins of books are not meant to be defaced like a temple. Yet I like to mark them myself with occasional notes. For that I use a pencil, which I like to think makes for a lesser violence, a temporary violation an eraser will set right. So I write on books very lightly. I do not stretch out the books and open them fully flat when I read. I open them at an angle so as not to break the spine of the book. I always read acutely, at an angle less than ninety degrees. If it is a new book I bought I would never settle down for more than the right angle. I dare not open books at an obtuse angle. That is an obtuse thing to do. It is depressing to look at books with heavily curved or broken spines. Or any book with physical flaws for that matter.

I was flipping the pages of A Lion in the House, a novel by Lina Espina-Moore about adultery. Published in 1980, it feels outdated now. Outdated not for being a period novel set in 1980 but for its heavy use of colloquial language of Manila of its time. It has its moments, like the scene of the wife rushing to get his husband from the apartment of his mistress, an apartment the husband was renting out. This section of the novel was recently included in Querida: An Anthology (2013). But overall the novel sounds false to me in 2016. The dialogues do not crackle. It relies too much on the slang, colloquialisms, and high society details of its period. Novels must be felt as if it is new. Its language must sound fresh for all time.

When I started the book I already flipped through its pages and saw the last page and I was vexed at an offending drawing, in ink. I never minded the musty smell and the browning, crispy pages of the old book. I never minded that the book was apparently read by someone else before it was sent to me. But that someone had the luxury of time to make doodles and lettering of a character's name. I was mad at the publisher (I ordered the book from the publisher, from their old stocks) for allowing this to happen and for sending me this vandalized book. I was mad at the vandal-reader for the indiscretion. However ambivalent I felt about the book, I did not like that it was tampered.

But I would not let this affect my reading. I continued reading and soldiered on to the last pages. The final, epistolary chapter was titled "Q.E.D." I finished the book. Then I discovered the "flaw" was not a flaw at all but part of the "text." But of course. This literary device was not new. I was amused.

Then everything fell into place. The philandering husband, Mr. Alberto de Leon, the "lion in the house", wrote in doodles. Of course. The stoic character whose thoughts were not always accessible in the book. A paper with nonsensical writing in it, from his "desk" illuminated something about his character. A thought balloon appeared, a thought bubble burst. The drawing expressed it all. His inflated ego, his narcissism, his vanity. Therein lay all his psychological complexity. Or his utter simplicity. Flawed as a person, as a lion, as a character. The book and its flaws. Quod erat demonstrandum.

12 September 2016

Shri-Bishaya

Shri-Bishaya by Ramon Muzones, translated from Hiligaynon by Ma. Cecilia Locsin-Nava (New Day Publishers, 2016)

|

| VISAYAN KADATUAN (ROYAL) COUPLE, FROM BOXER CODEX |

Shri-Bishaya by Ramon Muzones was first published as a serial novel in Hiligaynon magazine from 1969 to 1970, two years before the imposition of martial law. It borrowed its title from the ancient kingdom of Southeast Asia, the Srivijaya. It was a fictional adaptation and imaginative fusion of two famous epics from Panay Island in the Visayan region, central Philippines: the Maragtas and Hinilawod. The former was an embellished history of the origin of Visayan people who migrated from Borneo. Shri-Bishaya used the Maragtas as narrative framework of the novel, recounting how ten datus from Borneo fled to Panay Island to escape the despotic ruler Sultan Makatunaw. It described how the datus bought the island from Aetas and the challenges encountered by these new settlers to institute a free, independent government with a new set of laws and system of leadership.

Sultan Makatunaw was a transparent evil character, a composite of familiar rulers of today. He was mercurial, prone to sudden fits of violent temper. Makatunaw's rapacious greed and lust and blatant disregard for human rights reflected (and anticipated) the government under Ferdinand Marcos from late 1960s and onward until his toppling by a popular uprising and revolutionary government in 1986. In "The Maragtas Mystique", the novel's well-researched preface, translator Ma. Cecilia Locsin-Nava provided ample background in which to view this dictator novel as a form of resistance literature and postcolonial literature, notwithstanding the contested fictional nature of Maragtas as based on a "racist migration theory", according to historian William Henry Scott.

As a dictator novel, it described the injustices of Sultan Makatunaw in suspending due process for individuals who "live in fear and terror, because there is no telling who will be seized next from his home and will never see his family again." Just like in the time of Marcos, the sultan also forbade people from holding peaceful assemblies that might lead to the rise of resistance movements and a revolution to bring him down from power. Under Makatunaw's rule a new edict was issued wherein, based on reports by informers identifying the enemies of the state, "sans prior investigation, a person could be thrown into a river full of man-eating crocodiles, pilloried and fed to the ants, hanged on the lunok tree, buried neck-deep in hot sands, cut, quartered, and fed to wild beasts, and subjected to other forms of gruesome tortures."

Elsewhere, the sultan ordered the kidnapping of people suspected of going against him. "Many residents had been seized unawares in the middle of the night, torn from the embrace of their families, and banished without any trace of their whereabouts." This clearly anticipated the desaparecidos during the time of Marcos, and even up to the present.

As a maritime novel, a rare one in Philippine literature, the novel gave a glimpse of seafaring life at sea, albeit sometimes in magical realist fashion. Maritime wars fought at sea, encounters with cruel pirates, and fantastical sea creatures gave a mythical and adventurous flavor to the novel.

As a costumbrista novel and foundation epic recounting the building of a just and lawful society from a clean slate, it illumined some ancient Visayan character traits, customs, and laws (some already thankfully defunct) to instill disciple among the people.

"You are the oldest and the wisest among the datus I am leaving behind. In your hands I leave the management of the land and the lives of our people," Datu Puti continued.

"Do you have suggestions on what needs to be done?"

"I was thinking of several things. The land we bought is vast, there is a need for you to divide it, and give each datu his share."

"I intend to do that. I plan to give Datu Paiburong and Bangkaya their individual shares."

"That's a good start. But, there must be laws to govern the lives of our people. Have you thought about this?"

"Yes, I have thought up some laws, but there is a need to discuss these with the other datus first."

"Remember that you are starting afresh in this new land. You need to set strong foundations. What laws have you thought up?"

"It's true we are starting a new life in completely new surroundings. People have to work really hard so they will prosper. That is why I thought up a law that punishes heavily those who are lazy and do not provide for their daily needs."

"That's a good idea. What is the punishment for the lazy?"

"The lazy should be arrested and sold as a slave to an affluent family so he will learn the difficulty and value of domestic and farm work. After he learns his lesson he will be allowed to go back home. The cost of his sale will be returned to the buyer and he will no longer be considered a slave, but a timawa or free man who has been redeemed from indolence and is ready to live by the fruits of his labor. But, if it is discovered later that he has reverted back to his old ways, he will be arrested again, and banished into the jungle. He will not be allowed to mingle with other people lest he set a bad example."

"That is very good, Sumakwel. What else have you thought up?"

"Punish heavily the light-fingered. The fingers of a thief should be chopped off."

Datu Puti nodded his head.

Sumakwel continued to explain: "Only men who can support a family or families can marry more than one wife, and will be allowed to have children. The poor should not bear more than two children because it is hard to support or rear them. Children who cannot be supported, should be thrown into the river."

"Isn't it unfair to punish the innocent children for the crime of their parents?"

"This is a warning to those who would like to start a family but cannot afford to do so. The punishment is harsh, but there is a need for a man to learn at the outset his obligations to society and to the state. If he wants to start a family, he should work hard to support his dependents."

"Continue."

"If a man has gotten a woman with child and he abandons her because he has no intention of marrying her, the child should be killed because it is hard for a woman without a husband to support a child. Since the woman has brought shame to her family she cannot inherit anything. The man should be hunted down by the leaders of his district, and when he is caught but continues to refuse to marry the woman he has wronged, he and his child should be buried alive."

"Are you concerned about the honor of the family?"

"Yes, because I want the people to live righteous lives."

"Do you have other laws in mind?"

"I have, but they will have to wait until we will have held a meeting."

"I will not meddle with your affairs; I just want to remind you that we left Bornay because of the rapacity and brutality of the sultan. Let us not stain this new land with blood. This is not just a request, it is a bond because I am entrusting everything here to you."

"I will bear that in mind."

Datu Sumakwel, the leader and lawmaker entrusted by Datu Puti to lead the people prior to the latter's return to Bornay to assuage the anger of Sultan Makatunaw, was here outlining the rigid laws he would institute as leader. By contemporary standards, the laws were unsound and barbaric. And even the resolve of Datu Sumakwel to strictly implement these laws was ultimately tested when he found his own wife Kapinangan was having an affair with his own servant.

A terrible curse afflicted the life of Sumakwel, the wise datu whom everybody looked up to as the epitome of righteous living and good governance. Sumakwel could always be depended upon to implement the will of the people no matter what. But this crisis in his life was not a simple case of a wife's betrayal of her husband. It had other implications. If Kapinangan had committed the crime in Bornay, this would be no problem for Sumakwel but the trickery and treachery was committed in this new land, and there has, as yet, been no precedent regarding this.

The unfaithfulness of Kapinangan was a major plot element that tested the true character of the leader. Can the righteous and just Datu Sumakwel who wanted to set a good example to his people ever forgive the shameful crime committed against him? The novel was a forgiving medium to offer an unusual love story.

|

| VISAYAN KADATUAN (ROYAL) COUPLE, FROM BOXER CODEX |

As an adventure story, the novel was replete with magical elements and supernatural powers. When Datu Sumakwel and his babaylan Bangotbanwa climbed a mountain believed to be the home of their comet god, Lord Bulolakaw, they encountered amurukpok, an evil spirit dwelling in the jungle and exercising power over other evil spirits.

Bangotbanwa believed that they had simply disturbed the tranquillity of the denizens of the jungle who sent them the hideous creature. While Sumakwel had the highest regard for the babaylan, in his heart he believed that the world really harbors many evil elements that disturb human relations and hinder prosperity in life. There are malevolent spirits that are out to test man's capacity to take care of his own self.

The evil creatures they encountered, as well as the ones haunting the sea voyage of Datu Labawdungon and Datu Paibare, two main characters in a parallel story, came in various forms, but often in the form of a bakunawa or giant snake. The snake motif and imagery in the novel was like a premonition or prefiguration of the character of Sultan Makatunaw, who manifested such snake-like rapacity that his elimination became the central conundrum of the novel.

Sometimes they heard a screeching sound in front of them, sometimes beside them, and sometimes behind them akin to the hoot of a huge, unseen bird. At times, they would stop dead on their tracks because they would hear a pitiful, ear-splitting, sonorous cry as though someone was being tortured. However, they could not trace the origin of the sound. Their attention was also attracted by the boisterous roar of rushing waters but when they rushed to what they believed was its source, it would suddenly stop, and an eerie silence would suddenly descend on the jungle. They would also hear the grisly cackle of the muwa or the terrible roar of the bawa. But Sumakwel and Bangotbanwa were both busalians endowed with unusual physical prowess and superior kinaadman, fortified with the most potent talismans, curative himag, and tigadlom charm. They had penetrated many a jungle and tested their manhood matching wits with embattled kiwigs, and other wily and supernatural and preternatural creatures.

The charismatic power of the datus, derived from their kinaadman, was the same mythical magic and power possessed by the characters in the earlier translated Muzones novel Margosatubig: The Story of Salagunting. Shri-Bishaya was the next logical novel to be translated after Margosatubig, its companion novel. The two shared the author's thematic elements and predilection for magic, monsters, power plays, game of thrones, nation-building, and full-scale war.

Makatunaw had developed an expansionist design over many lands, and he harbored deep desire to punish the ten datus who fled from his kingdom. This novel abounds with political insights of the times. One could detect the current spate of untenable extrajudicial killings on this highly prescient novel.

"Don't believe we are without enemies. Put inside your head that we have secret enemies who are just lying in wait for the right opportunity. Therefore, spread out and disseminate the information that the kingdom is strong and ready to take on any comers. If you catch anybody doing something wrong against the kingdom, I give you the authority to exact the right punishment. You are fully aware that I know how to reward those who are loyal to me," stressed the sultan.

And ...

They celebrated their gathering with abundant food and wine. When the datus went back to their respective districts, life changed. They now enjoyed tremendous power, because they were given by the sultan the authority to exact punishment on any enemy of the kingdom. So, they abused their power. They showed everyone who was who inside the kingdom. [emphases supplied]

The long drawn out final showdown in the novel, between the soldiers of Sultan Makatunaw and the freedom fighters of Datu Labawdungon and Datu Paibare, was meticulous in its plotting. The sultan was fully aware of the brewing war in his kingdom and the people's increasing discontent at his brutality.

Labawdungon and his cohort Paibare were already set on living in another place, in Madyaas, the land where the Bornean datus escaped to. They came back to Bornay, the sultan's seat of power, ostensibly to unseat the sultan in order to satisfy the wishes of their prospective wives, and yet their connection to their former land was bound by kinship and loyalty to its people.

It was finally a race between him and the two datus to manufacture a "deadly weapon that can kill wholesale". The seemingly endless volley of stratagems and art of war tactics from both sides demonstrated how difficult it was to resist tyranny such that rebels and revolutionaries must offer everything just to secure an attractive future for their country.

"I know what you are thinking," said Labawdungon. "We all hold life dear, but more precious is freedom for which we should offer our lives. More important than ourselves is Bornay's future. If we want a peaceful and just rule, we must pay for it, no matter the price."

This statement was almost a tired template for nationalism – dying for one's country, exactly following Benedict Anderson's definition of a nation in his Imagined Communities (1983): "[A nation] is imagined as a community, because, regardless of the actual inequality and exploitation that may prevail in each, the nation is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship. Ultimately it is this fraternity that makes it possible, over the past two centuries, for so many millions of people, not so much to kill, as willingly to die for such limited imaginings."

Dying for the country was dying for a loved one. This equation was not inappropriate given that Labawdungon's motivation for declaring war on the Sultan was not only to free the people of Bornay from the sultan's tyrannical rule, but actually to secure the hand of a woman in marriage who only consented to become his wife if he could bring "the skull of Sultan Makatunaw" as bride price.

This remarkably prescient epico-historical novel did not sacrifice plausibility and authenticity for a diverting narrative of love and war. Dr. Locsin-Nava's translation overall captured the fantastical elements of evil and magic, its dialectical nature, and the aphorisms, hints of sarcasm, irony, and humor of the story. The dialogues often combined proverbs and a mix of idiomatic expressions. Here is a sample pile of idioms from its rich treasury of proverbs.

"It's impossible that nobody will bite if the bait is tasty," Sultan Makatunaw told his two trusted associates, Datu Hatib and Datu Garol. "I'm quite aware that there are people who even if you feed them with your hand will swallow your elbow," the sultan added. "These people are close to me, they help me, follow my every wish, and praise me to my face – that is, for as long as I have something to feed them and I am in power."

"Beloved Sultan," Datu Garol became anxious, "that has never entered my mind. Even if you subject me to a test, I will put my life on the line for the good of the kingdom."

"I'm not referring to the two of you," assured the sultan, "but to those who, while I am in power, praise me to my face but the moment I fall off my perch will devour me. Those people are with us while something is cooking in the pot but not if the food is gone."

"You are right, Beloved Sultan," Datu Garol agreed. "In this world there are bats and butterflies who will only alight when there is honey to suck. I'm sure you know that when a boat begins to list, rats spill over because they do not want to sink with the vessel."

"Because of this," the sultan continued, "we must extend and strengthen the reach of the kingdom so that people have something to suck on. For as long as their stomachs are full people will not entertain destructive thoughts. It is when the stomach growls because it is empty that we put ourselves in danger. We must guard our vessel well so that our enemies will not bore holes in our ship of state."

"It is easy to catch the enemy from the outside but difficult to flush out the enemy from within. It is like squeezing grain from unhulled rice," Datu Hatib added.

"That is what we need to focus on right now so that termites will not eat up the foundation of our house. People with full stomachs are no threat, what we should guard against are hungry people because a hungry man is an angry man," warned the sultan.

Would that this relentless, dynamic, and "proverbial" epic novel will have its epic share of readers.

Related post: http://booktrek.blogspot.com/2016/09/nick-joaquins-small-rowboat.html

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)