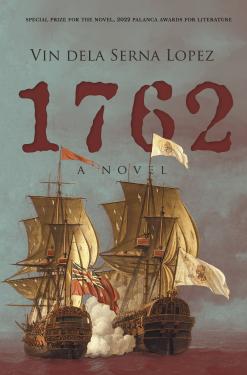

Vin dela Serna Lopez's 1762 (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2023) was one of the books that caught my attention in the Philippine Book Festival in Manila last June. I gravitated toward it for various reasons. Its arresting cover was a vision in burgundy. Two ships floating on a "wine-dark sea", clearly at odds with each other with all that heavy smoke in between; the prominent number-title reverse-embossed in that ink-blot, blood-like burgundy font; and the reddish British flag of the left ship waving. The synopsis at the back revealed the novel's backdrop: British invasion of Manila in 1762 which lasted for two years. It was a historical event largely ignored in fiction.

The novelist was scheduled to have an autograph signing in the Ateneo Press booth later that day. Thus I went around first on a book buying binge before coming back to the booth after lunch for an autograph. I snagged Vin's signature with this cryptic dedication.

How dare the author quote from Rizal's novel! The final words of Elias in the heartbreaking, penultimate chapter ("Christmas Eve") of the Noli. Yet this somehow made sense when I reached Chapter 4 ("Motto Stella") of 1762; and I now presume would make its full thematic connection to 1762 when I reach its end. (I am on page 140, Chapter 7 out of 33).

While I had my book autographed, I talked briefly with the novelist, telling him that the subject matter of his debut novel was something unexplored in fiction, with perhaps one exception which I mentioned to Vin: Linda Ty-Casper's first novel The Peninsulars (Bookmark, 1964), sadly still out of print.

In any case, here were my takeaways of 1762 after the first few chapters.1. This historical novel was attempting to unpack and synthesize the entire Spanish colonial history of the Filipinas. 1762 was just a post-colonial launching pad or platform, so to speak, to question the innumerable failings and betrayals that accompanied all nascent Philippine revolutions.

2. José Rizal was the guiding light of the novel. And I'm still feeling two ways about Chapter 4 which made for a provocative and weird (read: modernist) narrative approach. This chapter, written in the form of a play (disrupted from time to time by the main narrative thread), imagined a conversation between two novelists (Nicomedes and Amado, stand-in novelists whose identities were no surprise really from the moment you read their names) about the December 1896 execution of Rizal. It was a self-conscious commentary on selected moments in Philippine history, with betrayal and sacrifice and self-determination as running themes. I'm a bit ambivalent about this part because it somehow laid the history lessons too thickly: the primary reason I was both fascinated and repelled by Mike de Leon's 1999 meta-film Bayaning 3rd World. A time warp, a tear in the fabric of time, was deliberately opened here, but why rehash or repurpose an already familiar reading of history in a novel of history?

You are only rewriting what has been written before.

Nicomedes

I am no real historian, Nicomedes. I'm just a storyteller. Yet I have an obligation just the same

Amado

I will reassess my view of this chapter once I finish the book, and confirm if this chapter was the lynchpin that held the themes together or just pure literary provocation or something else. (Cirilo F. Bautista used a similar dialectical device in The Trilogy of Lazarus). Needless to say, Rizal animated the novel's ideas (in the first chapter alone, set in a Spanish galleon, class distinction among passengers and the back and forth of the action in the steamship's upper deck and lower deck reminded one of the opening chapters of El Filibusterismo).

3. The first acts of this novel were immersive and transporting. It had moments of beautiful writing and subtle comic brilliance. It was a well-researched, well-developed, and well-dressed steampunk novel. A summer blockbuster that did not scrimp on the budget.

Did I mention it was also a nautical war adventure and nation-mongering in the mold of Joseph Conrad's Nostromo? A theater of war with cinematic action sequences and imagery from the dramatic September 1762 Brentrance in Manila Bay to the Catholic capital's October capitulation two weeks later, the detailed reconstruction (and then destruction) of each rampart and church and bastion of Intramuros, the uniforms and clothing worn by soldiers and fighters from all sides, the maritime vocabulary, the catchy phrasing and seaworthy metaphors ("Busto suddenly found his troops cut off and forced to fend for themselves for the remainder of the night, repelling wave after wave of Sepoys and Lascars who kept bursting forth like ocean billows from their stronghold in Ermita."; "He passed them by with superficial indifference, passed by the sweep of the shore and the sea and the ships tarrying under the wisdom of unpredictable tides.").

The variety of war weapons used, the human and economic costs of war (sometimes graphic, often gruesome), the introduction of a fascinating cast of characters (an ensemble) and their blistering portraits and their Conradian motivations, the evocative language that bordered on Joaquinesquerie, with wayward phrases invoking irony and crackling with dissent and wit ("Archbishop Rojo cleared his throat of the phlegm of various possibilities."), the universal bottom-lines of a war economy, the natural history of empire, the looting and pillaging and rape (whether styled as 2022 Putinesque or 1762 British entry), political wrangling, prior to Brexit.

The Chinese settlers of the Parián, to whom Europeans had designated the epithet "Sangleys," were residing right in the shadows of imposing brass cannons protruding from a ravelin of the fortress city aptly called Intramuros, which had held the unimpregnated seat of Catholic authority in the Pacific since the end of the sixteenth century. Over four times larger than the Chinese district to its east, Intramuros was a gigantic brick and limestone metropolis defended by bastions thick as the illusions of a monarchist, parapets that crumbled like the ideals of a republican, and batteries that were as powerful yet as inconsistent as public opinion.

This period film was anything but grandiose production design and stirring musical score and snappy editing, although the battle scenes within the fortifications of Manila were

assembled with the same frenetic pacing of some of Pepys's diary entries. The novelist wanted to move back the reckoning of popular Filipino revolutionary history to an earlier date, further expanding a conception of that history as embedded in a world war.1

More than a rewinding of history (there's a breathless "rewind" scene of Rizal's execution), the novel fast forwarded to historical and timeless truths about human avarice and capacity for violence. If 1762's entrada was any indication, this first novel is bound to be a sui generis reading experience, a historical exercise that is romantic and disillusioning at the same time.

These were all tentative impressions for now. There was already, at the novel's onset, a preview or dry run of Philippine nationalism or nationalist tendencies, an early framing (or reframing) of a community imagined (or reimagined) in an age of globalization.2 There was, already, a novelistic excavation in the rubble pile of history. The story-teller as historian; the novelist as angel of history.3 Circa 1762.

Notes:

1. Read the novelist's impetus for writing the novel in "Why I decided to write a novel about Intramuros set in 1762" (link).

2. "[A nation] is imagined as a community, because, regardless of the actual

inequality and exploitation that may prevail in each, the nation is

always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship. Ultimately it is

this fraternity that makes it possible, over the past two centuries, for

so many millions of people, not so much to kill, as willingly to die

for such limited imaginings." (Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism). See also his analysis of Rizal's writings and final days and their connections to Western anarchist thinking in Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination aka The Age of Globalization: Anarchists and the Anticolonial Imagination.

3. In Walter Benjamin's formulation: "This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned

toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single

catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in

front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and

make whole what has been smashed." ("Theses on the Philosophy of History", in Illuminations, translated by Harry Zohn, edited by Hannah Arendt).