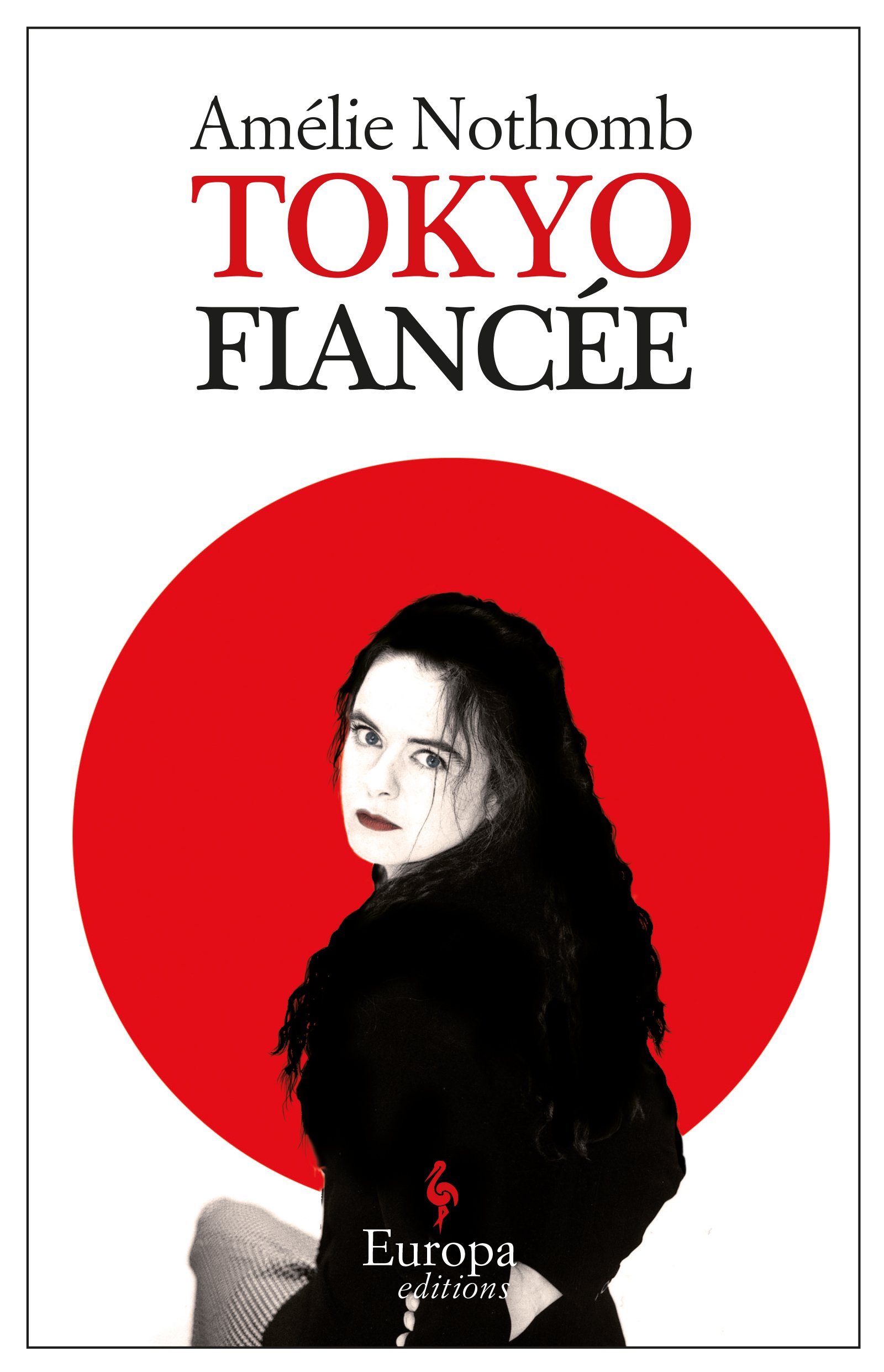

I'm in the middle of reading Tokyo Fiancée (Europa Editions, 2009) by the Belgian novelist Amélie Nothomb, translated from French by Alison Anderson. The original title was Ni d'Eve ni d'Adam. "With my six thousand yen I could buy six golden apples at the supermarket", said page 7. "Adam surely owed that much to Eve." The publishers, who wanted to exoticize the Japanese connection and deemphasize the forbidden fruit, owed much to the reader.

What's propelling me to read a Nothomb novel--my third this year after First Blood (her most recently translated) and Life Form; eighth novel so far since I started deciphering her ideograms in translation--was the question of language. A Nothomb novel was always ever a questioning of absolutes, of the default role of language in miscommunication, how language acquisition--often at the center of her books; see, for example, The Character of Rain) was more nuanced than we care to observe and how the clash of cultures was a post-Babel myth.

Nothomb's main characters were polymaths. They knew many languages. They had "linguistic intuition." This trait made her characters great readers of manners and people. When they read something in a foreign language (say, Japanese), they understand it not because they have a photographic memory of Japanese "characters" (ideogram) but because they have a photographic understanding of signs and symbols, the constituent parts of language. Declared her novelist-character in Life Form: "I am capable of going a very long way in the name of my semantic convictions. Language, for me, is the highest degree of reality."

Ever the ironist, the novelist was chill in her approach to

narration. Her scenes were comic set pieces perfectly timed to explode in punchlines.

In their economy of exposition, her novels, in translation, were stand-up comedies. I always ended up reading her novels in tears.

Of the three Nothomb novels I read so far this year, Tokyo Fiancée was proving to be a favorite comfort food (although First Blood possibly contain the raison d'etre of the novelist's literary enterprise). In the story of two interracial lovers (Belgian female and Japanese male) trying to reconcile their feelings through learning each other's language and culture, the novelist managed to insert commentary on other novelists like Yukio Mishima and Marguerite Duras.

Her fictional defense of Duras was a spirited defense of the other.

I could not read this with a straight face. Though this did not dampen my interest in adding to my reading list Duras's screenplay (or watching) Hiroshima mon amour. And yes, no matter how the novelist subverted that literary assessment later, I recognized in that reaction of reading a difficult novel the same anger and frustration I felt when reading Duras's The Lover. Angry, frustrated. Like reading Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino even, like reading Clarice Lispector's Near to the Wild Heart, like watching a ponderous film by Lav Diaz. One was angry and frustrated because one was stupefied and repulsed at the same time. Maybe because one has recognized the folly of reading or watching a masterpiece.

The hunger felt by an interracial couple after discussing the screenplay about an interracial couple was masterfully juxtaposed with the eating of a Japanese delicacy.

The food, like a difficult masterpiece novel, was a labor of love. "It would be impossible to overstate how fervently I devoted myself to the cause of French literature," thus the narrator ended her literary task after reading to her Japanese lover a few more passages from the French screenplay.

No comments:

Post a Comment