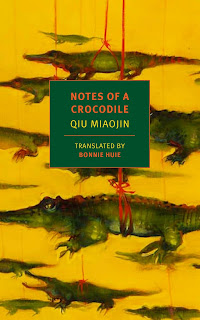

In Notes of a Crocodile, translated by Bonnie Huie, Qiu Miaojin had her protagonist describe two films from France. The first, Mauvais Sang (1986), directed by then-26 years old Leos Carax, starred Denis Lavant and Juliette Binoche and had a intriguing premise.

A sexually transmitted disease called STBO is sweeping the country; it’s spread by having sex without emotional involvement, and most of its victims are teenagers who make love out of curiosity rather than commitment. A woman hires two men to steal the serum, which has been locked away in an inaccessible government building. [from Wikipedia]

The narrator of the novel was a female writing student who developed feelings for a female classmate. Her assessment of the Carax film made me want to watch it. Spoiler alert.

Not another Godard movie. A more youthful French film. Its male protagonist is built like a lizard and clearly has traces of crocodile in his blood. All the other men are short and stout and bald. They're all ugly old men in this film, aside from this sight-for-sore-eyes of a young Adonis in the lead role. The director is a contemporary master of aesthetics.

"I must ascend, not descend," the protagonist declares. As he nears his final moments, the female lead embraces him from behind, and he resists. It's moving beyond words. He closes his eyes with a dramatic flutter and utters his last words: "It's hard being an honest child." After he dies, a hideous old man squeezes a single blue tear out of his closed eyes. There's essentially no way the lizard can be honest. Even as it rolls over and turns its white belly up, it must take its hidden tears for its lover to the grave.

Her wry descriptions of the characters' physical appearances and the movie's rather preposterous yet emotive plot was already evident from the trailer alone. See it here.

Yet another inoculating experience for the narrators was Betty Blue, which also appeared in 1986 and was directed by Jean-Jacques Beineix. The synopsis in Criterion was written by a master of the Blurbing Syndrome.

When the easygoing would-be novelist Zorg (Jean-Hugues Anglade) meets the tempestuous Betty (Béatrice Dalle, in a magnetic breakout performance) in a sunbaked French beach town, it’s the beginning of a whirlwind love affair that sees the pair turn their backs on conventional society in favor of the hedonistic pursuit of freedom, adventure, and carnal pleasure. But as the increasingly erratic Betty’s grip on reality begins to falter, Zorg finds himself willing to do things he never expected to protect both her fragile sanity and their tenuous existence together. Adapted from the hit novel 37°2 le matin by Philippe Djian, Jean-Jacques Beineix’s art-house smash—presented here in its extended director’s cut—is a sexy, crazy, careening joyride of a romance that burns with the passion and beyond-reason fervor of all-consuming love. [from Criterion; see also Betty Blue at The Modern Novel]

Given the subject matter of Notes of a Crocodile and its anti-sentimental tone and its cinematic approach to narrative (i.e., a sequence of pithy scenes with efficient images and understated yet bursting emotions), one could appreciate why these two films were singled out by the novelist. The narrator's review of the second film was a window into her soul. Second alerte spoiler.

It's relatively institutional fare. A French film made for a young mainstream audience. Just how is it made for them? There are only two colors, blue and yellow, which makes things easy to remember, and aside from the two protagonists—a man and a woman—there's no one else on earth. Time glides by in the film without so much as half a struggle or a long conversation. ...

The best thing about the entire film is when the main couple's friend, upon hearing news of his mother's death, lies in bed paralyzed, and other people have to dress him for the funeral and tie his necktie, which is adorned with naked ladies. The tears streaming down his face make you want to explode laughing. The female protagonist, Betty, says, "Life always had it in for me." She gouges out her own eyes and is sent to a mental institution, where they strap her to a bed. The male protagonist says, "No one can keep the two of us apart." He disguises himself as a woman in order to sneak into the institution, and with a pillow, smothers Betty to death. At that moment, his face, exquisitely white, radiates a ghastly feminine beauty. The director uses a crazy love to curse the hand of fate. Fair enough, though the last bit will make you gag on your popcorn and soda.

...

... The second film is deceptive in its approach. It tricks you into thinking that you're not on the road to nausea, until the very end, when the truth becomes clear.

The sinister undercurrent was already apparent in the trailer of the director's cut (link). I could sense—and I wanted to be proven wrong—that this novel had something deceptive too in its sleeve. "Anyone with eyes, even if they're color-blind," the narrator thought, "can sit with popcorn in one hand and soda in the other, and leisurely watch the whole thing. Fair enough."

***

The watching of a film may be deliberate or a happenstance. And yet the rules of film making were already made visible. In "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction", Walter Benjamin wrote that "It is inherent in the technique of the film as well as that of sports that everybody who witnesses its accomplishments is somewhat of an expert." The democratized access to the movie theater and television—at least during pre-pandemic times—made film watching as ubiquitous as watching sports in stadiums and on TV. Benjamin's thoughts on the reproducibility of art and films were made prior to the digital age and film streaming devices—not to mention the rise and fall of blogging and the rise and rise of vlogging and content creation—and yet the ideas he propounded in his essay were all the more validated by the technological advances.

For Benjamin, every moviegoer was a film critic, but not every one of them was aware that they were.

The film makes the cult value recede into the background not only by putting the public in the position of the critic, but also by the fact that at the movies this position requires no attention. The public is an examiner, but an absent-minded one. [tr. Harry Zohn, from Illuminations]

With "popcorn in one hand and soda in the other" the watcher was assaulted by a barrage of moving images, which for Benjamin could induce a kind of vertigo and produce a violent crisis of imagination, a "shock effect" which was akin to the experience of Dadaist art in (real) time and space.

Dadaistic activities actually assured a rather vehement distraction by making works of art the center of scandal. One requirement was foremost: to outrage the public.

From an alluring appearance of persuasive structure of sound the work of art of the Dadaists became an instrument of ballistics. It hit the spectator like a bullet, it happened to him, thus acquiring a tactile quality. It promoted a demand for the film, the distracting element of which is also primarily tactile, being based on changes of place and focus which periodically assail the spectator. Let us compare the screen on which a film unfolds with the canvas of a painting. The painting invites the spectator to contemplation; before it the spectator can abandon himself to his associations. Before the movie frame he cannot do so. No sooner has his eye grasped a scene than it is already changed. It cannot be arrested. Duhamel, who detests the film and knows nothing of its significance, though something of its structure, notes this circumstance as follows: “I can no longer think what I want to think. My thoughts have been replaced by moving images.” The spectator’s process of association in view of these images is indeed interrupted by their constant, sudden change. This constitutes the shock effect of the film, which, like all shocks, should be cushioned by heightened presence of mind. By means of its technical structure, the film has taken the physical shock effect out of the wrappers in which Dadaism had, as it were, kept it inside the moral, shock effect.

The immediate visual and auditory gratifications afforded by the binge watching of scenes after scenes of life and counter-life produced an alternative vista and borrowed time for the watcher. Benjamin thus indirectly defined—or came close to—what could constitute a classic in art (literature or painting or film). The relevance or the life of the art, its longevity, its stature and resilience as a classic—these were not contingent on present readers or viewers or watchers. If it survived at all—in J. M. Coetzee's definition of a classic as a survivor—after the initial onslaught of the present, then it must have done so because it was created using the template of the future. Its concerns were, overtly or covertly, futuristic. Because (futuristic) art could aspire for future appreciation, the true audience of art are the future people who stumbled upon it at a future time. "One of the foremost tasks of art," said Benjamin, "has always been the creation of a demand which could be fully satisfied only later."

The history of every art form shows critical epochs in which a certain art form aspires to effects which could be fully obtained only with a changed technical standard, that is to say, in a new art form. The extravagances and crudities of art which thus appear, particularly in the so-called decadent epochs, actually arise from the nucleus of its richest historical energies. In recent years, such barbarisms were abundant in Dadaism. It is only now that its impulse becomes discernible: Dadaism attempted to create by pictorial—and literary—means the effects which the public today seeks in the film.

Every fundamentally new, pioneering creation of demands will carry beyond its goal.

[emphasis added]

The classic was an attempt at something new; its newness was only made more apparent after a certain time has elapsed when the technical (or literary) standard, alongside hidden critical and historical forces and movements, had changed. The classic remained steadfast in emitting hidden energies long after the first outrage or shock or awe at the conflagration or war of the senses had settled or died down.

The watcher's assumption of the role of the film critic mirrored that of the author's reader. As Benjamin noted, "At any moment the reader is ready to turn into a writer. As expert, which he had to become willy-nilly in an extremely specialized work process, even if only in some minor respect, the reader gains access to authorship." Truly, the Quixote can be subsumed by the pen of Pierre Menard.

***

What of Qiu Miaojin's literary antecedents, Dadaist or otherwise? The first paragraphs of the posthumously published novel already gave away her reading list.

July 20, 1991. Picked up my college diploma at the service window of the registrar's office. It was so big I had to carry it with both hands. I dropped it twice while walking across campus. The first time it fell in the mud by the sidewalk, and I wiped the mud off with my shirt. The second time the wind blew it away. I chased after it ruefully. The corners were bent. In my heart, I held back a pitiful laugh.

When you visit, will you bring me some presents? the Crocodile wanted to know.

Very well, I'll bring you new hand-sewn lingerie, said Osamu Dazai.

I'll give you the most beautiful picture frame on earth, would you like that? asked Yukio Mishima.

I'll plaster your bathroom walls with copies of my Waseda degree, said Haruki Murakami.

And that's how it all began. Enter cartoon music (insert Two Tigers closing theme).

Dazai, Mishima, and Murakami—all suicides except for the latter. Notes of a Crocodile was written in 1994, a year before Qiu Miaojin's suicide in Paris, where she studied and directed a short film. She was 26 years old.

Murakami's published novels before 1991 (the year in the notebook entry) were arguably his best output (i.e., before Murakami's commercial literary appeal catapulted him into literary stardom and somehow, probably, contaminated his magical realist worldview and eroded his discipline for world-building). These were my favorite works of Murakami: the world of A Wild Sheep Chase, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, Norwegian Wood, and Dance Dance Dance. The magic in these novels was restrained and unforced; their tones were polished, at a time when the quality of his novels was unburdened by overanalyzing current events and the technical shift from typewriter/word processor to desktop computer.

The surrealist beginning of the entrada already hinted at an idiosyncratic voice and temper of the narrator, her aura of literary knowingness, the tinge of easygoing loneliness intercut with lighthearted and cinematic moments of emotional eruptions, linear and non-linear. "Nauseating is nauseating," the novelist quoted from Mauvais Sang. The tactile details of this tactile novel may prove to be a memorable watch, attuned as it is to colors blue and yellow and presumably the truth, which at this point is not yet clear, or may never be, but no one is complaining. Tactile is tactile.

Enter: music from Two Tigers.

Belated thanks for this post, Rise. I like its comp lit-like vibe even though I only remember having seen one of the two films for sure (it's been a while). What an unexpected concatenation of references--plus Benjamin! Hope you have more writing in store like this someday (I have some catching up to do, of course, until then). Cheers.

ReplyDeleteHola, Richard. Nice to hear from you again. Muchas gracias for the comment. Reminded me that I need to revisit Benjamin. Hope all is well with you.

ReplyDeleteAnonymous = Rise. Why can’t I seem to log onto my account!

ReplyDelete