To this day, I've never understood my fear. Where does it come from? I'd been keeping my deviant sexual desires in check for most of my adolescent and college years. I reassured myself that I'd done nothing wrong. It felt like the fear was coming from inside of me. I never did anything to attract it, nor did I choose to be this way. I had no hand whatsoever in shaping the self that was crawling with fear. Yet I grew into exactly that: a carnal being stirring the cement of fear with every step toward adulthood. Since I feared my sexual desires and who I fundamentally was, fear stirred up even deeper fears. My life was reduced to that of some hideous beast. I felt as if I had to hide in a cave, lest anyone discover my true nature.

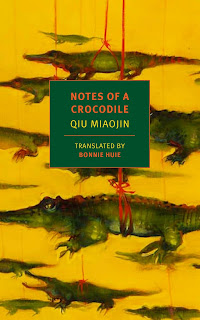

Qiu Miaojin's Notes of a Crocodile (New York Review Books: 2017), translated from the Chinese by Bonnie Huie, was a novel of introspection, so honest and unflinching in its confessions and self-questioning. Lazi, the female protagonist, was programmed to fear, like any other human being always put on the spot to reconcile herself with herself, with others, with society. It was a novel driven by sexual identity crises, filled with characters unable to fully function due to fears and reprisals. The right to play the game was only accorded to two kinds of players. The novel's sex problematique:

Two very different types of people, mutual attraction. And for what reason? It’s hard to believe, this thing beyond the imagination of the chess game known as the human condition. It’s based on the gender binary, which stems from the duality of yin and yang, or some unspeakable evil. But humanity says it’s a biological construct: penis vs. vagina, chest hair vs. breasts, beard vs. long hair. Penis + chest hair + beard = masculine; vagina + breasts + long hair = feminine. Male plugs into female like key into lock, and as a product of that coupling, babies get punched out. This product is the only object that can fill a square on the chessboard. All that is neither masculine nor feminine becomes sexless and is cast into the freezing-cold waters outside the line of demarcation, into an even wider demarcated zone. Man’s greatest suffering is born of mistreatment by his fellow man.

The text of the novel was spread out over eight notebook entries, numbered consecutively and which served as the novel's chapters. The texts inside the notebooks were a pastiche of journal writing, love letters and break up letters, an ongoing satire on a Crocodile and its adventures in a scandalized society who could not imagine the life of a Crocodile (the Crocodile being a stand-in for the narrator and her identity as a lesbian), references to films and novels (e.g., Norwegian Wood by Murakami Haruki, The Box Man and The Face of Another by Abe Kobo), references to music and pop culture (e.g., news about Lady Diana), flashbacks and reminiscences of friendships and doomed love affairs with both sexes. Lazi called her eight notebooks "manuals", the reading of which, rather than the writing, illustrated her "process".

Based on ten massive journals' worth of material, I wrote eight manuals that can be read as admonitions for young people. A clean transcription was made using a ballpoint pen before each notebook was stuffed into the bottom of a drawer. Whenever my memory failed me, I would take out a notebook and look at it, and go over the events that made me who I am. They illustrate the process.

The novel was marked by fluidity of gender in the interaction of its characters: "When we were together, my masculine and feminine sides reached their highest state of dialectical tension. It was the same for him, and he knew that it was his optimal state."

After two French films (see previous post), sure enough we got more references to films. Valley of the Dolls (1967): the trailer alone was oozing with sappiness; the film must be a revolutionary template for instant gratification in soap operas. Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1987): another adaptation, from a famed novella of Gabriel García Márquez, reviewed elsewhere in this blog. Lazi's synopsis brought one back to the fatalistic atmosphere of García Márquez, but it more or less refracted her view of obsessive love.

The male protagonist searches everywhere for the woman of his dreams. After "selecting" the female protagonist with only a glance, he racks his brain thinking of ways to lavish his riches on her before eventually taking her as his bride. But on their wedding night, he discovers that his bride isn't a virgin. That evening, the half-undressed, sobbing bride is "sent back". And so the bride's family takes her in, and every day, she sends him a letter. In the final scene, the male protagonist, carrying an enormous sack of letters, enters the courtyard, where the female lead awaits him. "The journey is littered with letters...."

...

Shui Ling didn't know it, but when I saw Chronicle of a Death Foretold and discovered that the bride wasn't a virgin, I followed in the groom's footsteps. [first ellipsis in the translation]

Lazi herself was an inveterate writer of letters to her lovers. It made the novel conversational and the revelations and confessions more intimately voiced. Lazi followed in the groom's footsteps after discovering his bride's devirginized status. Yet she also followed the obsessive patience of the bride in writing letter after letter to the groom who spurned her. (The fate of Santiago Nasar, the man who deflowered the bride and murdered in broad daylight, was not mentioned.) Qiu Miaojin's second posthumous novel, Last Words from Montmartre, was apparently more love letters churned out.

Lazi's notebooks compiled ultra-honest portrayals of herself and her friends as spiritually wounded people. In Notes of a Crocodile, the characters' sexuality seemed to contaminate their relationships and ability to forge and sustain love affairs. For them, the force of love was like an unstable radioactive substance they could not control however much they wanted to pin it down. So these characters underwent suffering and transformations to cope with their damaged relationships. In the end they destroy themselves and the objects of their love.

Elsewhere: Andrey Tarkovsky's Nostalghia (1983). Then: van Gogh's The Potato Eaters. It's as if Lazi's memory filtered the art forms her senses encountered and made of them scrap materials for her readymade project. She was seeing herself in the painting, the central figure, her back turned. "How can we get to know each other?" a woman intoned (in subtitle) near the end of the trailer for Nostalghia. "By abolishing the frontiers," a man responded. Easier said than done.

Whether I was delivering a rambling speech or serving potatoes, I reeked of a degenerative disease of the spirit, the result of having been sequestered for too long. The layer of glass had grown thicker and harder to shatter.

Like "damaged goods" as one character described himself, Lazi was spiritually broken. It came to the point that she could invoke a Kafkaesque transformation. What if you suddenly woke up one day to find that you'd turned into a crocodile, what would you do then? asked Pro-Croc, a satirical character in the parallel universe of Lazi's notebooks/manuals. The choice of a crocodile as alter-ego was inspired: a beast feared by every one, and is in turn constantly hounded/harassed/persecuted for its animal nature whenever it goes out to hunt for food. Living in fear, the Crocodile suited up itself and descended from its habitat to disturb society's binary conception of sex.

"Hey, we should found a gender-free society and monopolize all the public restrooms!" I was elated at the idea. He didn't have to explain. He too could envision the manual I was writing about my own experiences. I decided to stop pressuring myself to state those experiences explicitly. ... I would speak up when the time was right.

In Qiu Miaojin's manuals, her "admonitions for young people", a literary project was conceived: the dream of a gender-free society, whose fluid and post-gender relations of the sexes lead to trust and love and understanding contra "mistreatment" of fellow human beings. Where crocodiles were dealt with without fanfare and fear.

All of which point to Qiu Miaojin's novel as a premonitory exercise of suicide. The text, which included a short extract from Suicide Studies, a presumed extant text, was a foreboding of the end point. In the company of Enrique Vila-Matas's literary silences, the suicides occupy a point where their death terminated their message. But it was too late to reverse what already survived them. The final statement in Notebook #2 was as close to a mission statement there is: As long as I'm alive and able, I won't stop talking about humanity and all of its fears.

This cold novel had some powerful writing in it, dissecting friendships and love affairs with cold-blooded precision and a reptilian prose giving the feels. It could not instantly abolish frontiers and lead to dramatic changes in gender relations but it could pose questions and deliver unforgettable images in freeze frame. Like how Lazi "was reminded of how in Truffaut's The 400 Blows, the boy breaks out of prison and runs to the sea, and that final close-up of the expression on his face."

Truffaut's iconic last scene in The 400 Blows was addressed directly to the viewer. The novelist just happened to let her protagonist remember the cinematic shot and relive the drama behind the ambiguity.

|

| Image from Criterion |