▼

▼

08 December 2016

A handful of books

If I would recommend my favorite reads of the year, I would go for the ones that grow in stature in my mind. Out of the forty-odd books from various genre I read this year, I choose to highlight novels that I feel I have never actually finished reading because they linger still in my memory. Some of these novels I did not instantly "like" or "love" that much during the time I read them, "like" and "love" I find to be terms that are transcended by only a handful of novels. These books challenged my perspective of the world and disrupted my thought processes. In hindsight, I look at my "favorite" reads as resisting the likeability factor. César Aira talks of "retrospective comprehension" as the advantage of literature over other artistic forms. Novels allow readers to form mental pictures from words, and these words had the potential to turn upside down our deeply held assumptions at the start of book because of a carefully withheld detail or fact, the revelation of which at the last page could bring a new level of understanding to what has previously transpired.

Here then are five novels that made my year. They are translated from four languages: Italian, Filipino, Cebuano, and Hiligaynon. The four books translated from Philippine languages are not readily available outside the country – in fact, some of them are even hard to find in my country; one needs to search them out! – so it's like I am offering a reading list of possibilities or potentialities. It's like a list of fictional books from the Invisible Library, nonexistent in many parts of the world and could only live in the imagination of some readers. So here they are: their obscurity could not dim their greatness.

1. Contempt by Alberto Moravia, translated from the Italian by Angus Davidson

My contempt for the main character and his funky first person narration could not dampen my admiration for its brilliant take on the superficiality of modern life weighed down by materialism and political correctness. The unreliable narration was perhaps rivaled only by The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro. (review)

2. Ang Inahan ni Mila (Mila's Mother) by Austregelina Espina-Moore, translated from Cebuano by Hope Sabanpan-Yu

Of the four novels by Espina-Moore that I've read, this one stands out for the comedy and the roundness of its titular character, a domineering mother and wife and a villainous force to reckon with. Mila's mother is a quirky woman whose lot in life may be determined by her past struggles and class prejudices. As the novel progresses, one discovers much else about her character that made her an altogether sympathetic figure. (review)

3. Juanita Cruz by Magdalena Gonzaga Jalandoni, translated from Hiligaynon by Ofelia Ledesma Jalandoni

Another first person novel told in a perfectly calibrated voice of its eponymous narrator, Juanita Cruz is an immersive and transportive novel of adventure of a rich girl escaping her upper class upbringing to become a fully empowered woman.

In my review I take note that Jalandoni, along with Ramon Muzones and many other deserving novelists, was several times bypassed or not even considered for the award of National Artist of Literature. The sad thing is, from a dozen or so already included in the roster of Philippine National Artists, a couple of writers does not have an outstanding body of work to speak of. It is shocking to see how the cultural arbiters failed to honor deserving novelists from other regions and simply could not distinguish the difference between cultural workers and true artists. I wonder what future is in store for the literature of a country whose best writers were not even accorded the full respect and honor due to them. (Pardon the rant, my review post is in here.)

4. Shri-Bishaya by Ramon Muzones, translated from Hiligaynon by Ma. Cecilia Locsin-Nava

My review of this book does not really give full justice to its epic grandeur. I mean, in addition to the foundation myth and love story, I have not even described the superlatively dramatized fight scenes in the book. There is the competition between two warring factions on who would be the first to produce the powerful weapon of lantakas and kirabon. There are supernatural encounters with giant snakes and monsters, well-choreographed maritime battles, and guerrilla warfare on the ground.

This is simply a well-written action fantasy. Its political ramifications, however, are still as relevant as today's news. When the book described repeatedly – too many times for one's comfort – that "sans prior investigation, a person could be thrown into a river full of man-eating crocodiles, pilloried and fed to the ants, hanged on the lunok tree, buried neck-deep in hot sands, cut, quartered, and fed to wild beasts, and subjected to other forms of gruesome tortures", one could be forgiven for glossing over the exaggerations present in a fictional narrative. But once confronted in real life by gruesome allegations involving crocodiles, quartering, dumping, etc., then the reader can only surmise that between allegations in life and in fiction, one or both versions must be true.

If only someone is bold enough to adapt this into a mini-series. Enough of the second-rate, trashy imitation fantasies that are celebrated in TV today. (review)

5. Typewriter Altar by Luna Sicat Cleto, translated from Filipino by Marne L. Kilates

In Typewriter Altar, a middle-aged would-be writer looks back on her childhood and adult life full of domestic baggage and angst. She is also full of unexplained guilt and grief whose magnitudes seemed to exceed those of the fanatic carriers of original sin. The writer's problematic relationship with her father is the central pivot of the story. The episodic story revealed the interior life of a writer struggling with her craft, with demons and ghosts, and with the poetic allure of melancholic existence. (review)

04 December 2016

El consejo de los dioses

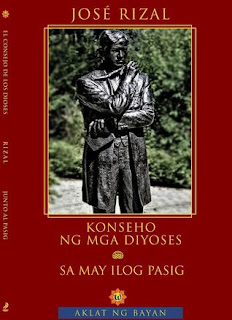

"El consejo de los dioses" in Konseho ng mga Diyoses; Sa May Ilog Pasig (El Consejo de los Dioses; Junto al Pasig) by José Rizal, translated by Virgilio S. Almario and Michael M. Coroza (Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, 2016) [dual language edition]

On 23 April 1880, the Liceo Artistico Literario de Manila accepted entries for an annual writing contest to commemorate the 264th anniversary of the death of Miguel de Cervantes. For that literary competition the nineteen-year old José Rizal (1861-1986) submitted a one-act play about an unusual literary competition called El consejo de los dioses. In his play, the gods reunited in Olympus to serve as literary jurors and choose from among three writers the most deserving of immortality. The finalists were: Homer, Virgil, and Cervantes. No, this was not a conventional Nobel Prize for Literature. The judging panel could not arrive at a consensus choice from among the three formidable writers. Each writer had his own celestial champion. The heated deliberations of the gods almost resulted to a Ragnarök of sorts. If not for the wise intervention of Jupiter and one impartial judge, the brewing conflict among the judges would have resulted to a civil war among the divine.

The play opened with Jupiter announcing the idea behind the literary contest, the three major prizes to be won by the laureate (a soldier's trumpet, a lyre, and a crown of laurel, all magnificently crafted), plus the criteria and scope of judging. Jupiter's motive behind the contest – commemorating the triumph of the deities against the rebellion of Titans now incarcerated in Tartarus – was similar to the nasty Hunger Games.

JUPITER: Nagkaroon ng isang panahon, mga kataas-taasang diyoses, na ang mga suwail na anak ni Terra ay nagtangkang makaakyat sa Olimpo upang agawin sa akin ang kaharian, sa pamamagitan ng pagpapatong-patong ng mga bundok. At natupad sana ang kanilang nasà, nang walang anumang alinlangan, kung hindi nagtulong ang inyong mga bisig at ang kakila-kilabot kong mga kidlat upang ihulog silá sa Tartaro at ibaón ang iba sa púsod ng naglalagablab na Etna. Ang ganitong kalugod-lugod na pangyayari ay nais kong ipagdiwang nang buong dingal, na siyáng nababagay sa mga inmortal [...] Kayâ nga, ako, ang Kataas-taasan sa mga diyoses, ay nagpapasiyang ang pagdiriwang na ito ay magsimula sa isang timpalak-panitik. Ako'y may isang marangyang trumpeta ng mandirigma, isang lira, at isang koronang lawrel at pawang napakarikit ang pagkakagawa. [...] Ang naturang tatlong bagay ay magkakasinghalaga, at ang makilálang may napakataas na ambag para sa pagkalinang sa panitikan at sa mga katangian ng puso't damdamin ay siyáng magkakamit ng nasabing kahang-hangang hiyas. Ipakilála nga ninyo sa akin na ang mortal na sang-ayon sa inyong paghatol ay karapat-dapat na tumanggap ng mga ito.*

–

JÚPITER.

Hubo un tiempo, excelsos dioses, en que los soberbios hijos de la tierra pretendieron escalar el Olimpo y arrebatarme el imperio, acumulando montes sobre montes, y lo hubieran conseguido, sin duda alguna, si vuestros brazos y mis terribles rayos no los hubieran precipitado al Tártaro, sepultando á los otros en las entrañas de la ardiente Etna. Tan fausto acontecimiento deseo celebrar con la pompa de los inmortales [...] Así, que yo, el Soberano de los dioses, quiero que comience la fiesta con un certamen literario. Tengo una soberbia trompa guerrera, una lira y una corona de laurel esmeradamente fabricadas [...] Las tres valen igualmente, y el que haya cultivado mejor las letras y las virtudes, ese será el dueño de tan magníficas alhajas. Presentadme, pues, vosotros e mortal que juzguéis digno de merecerlas.

One by one, the bookworm-gods spoke and nominated their favorite writer. Juno made a case for Homer on account of his bold and daring ("matapang at pangahas") Iliad and his thoughtful and restrained ("mapaglimi at mapagtimping") Odyssey.

After Juno, Venus took center stage and respectfully objected to the former's choice. She herself made an impassioned plea for Virgil who celebrated the life of her son Aeneas (yes, these gods had their own interest in mind, they were not about to inhibit themselves from the proceedings!). She pointed out to Jupiter the great and merciful quality of Aeneas compared to the fiery temperament of Achilles. For her, Virgil satisfied all the criteria of the singular writer Jupiter was looking for: the one with a substantial contribution to the cultivation of literature and the heart ("may napakataas na ambag para sa pagkalinang sa panitikan at sa mga katangian ng puso't damdamin" / "el que haya cultivado mejor las letras y las virtudes").

A word war ensued between Venus and Juno, after which Minerva took the stage and made an equally heartrending plea for Cervantes, the "son of Spain" who was at first a neglected and pitiful figure (Minerva was alluding to the adventures of Cervantes as a soldier before becoming a novelist) before giving birth to the light his masterpiece.

Ang Quijote, ang kanyang kahanga-hangang anak, ay isang latigong nagpaparusa at nagwawasto ng mga kamalian, nagpapabulwak hindi ng dugo kundi ng halakhak. Isa itong nektar na hinaluan ng mga birtud ng isangmapait na medisina; isang kamay na humahaplos ngunit matigas na pumapatnubay sa mga pasyon ng tao.

–

EL QUIJOTE, su parto grandioso, es el látigo que castiga la risa; es el néctar que encierra las virtudes de la amarga medicina; es la mano halagüeña que guía enérgica á las pasiones humanas.

And then Minerva discussed some more the form of enlightenment Cervantes brought not only to his land but to other shores. Apollo then spoke to second Minerva's appreciation of the Spanish novelist, with this parenthetical quip between his lofty statements: "I implore you not to assume I am partial to Cervantes because he devoted many beautiful pages to me." ("Ipinakikiusap ko sa inyo na huwag ipalagay na ako'y mahilig kay CERVANTES sapagkat ako'y pinag-uukulan ng kanyang maraming magagandang pahina." / "Os ruego no me tachéis de apasionado porque CERVANTES me haya dedicado muchas de sus bellas páginas.")

The deliberation of the gods continued becoming less and less godlike (read: uncivil), with some of them resorting to the oldest tricks in the book: appeal to pity and argumentum ad hominem.

Marte (Mars) joined the fray by slamming Cervantes who apparently defamed him in the novel and ridiculed his exploits ("ang aklat na nagpabagsak sa lup ng aking kaluwalhatian at umuyam sa akong mga nagawa" / "el libro que echa al suelo mi gloria y ridiculiza mis hazañas se alce victorioso"). The angry Marte even marched to the middle of the hall, issued a challenge with his defiant eyes, and brandished his sword.

Minerva spoke again in support of Cervantes and contextualized the Spanish writer's position on the use of arms and letters. (I think she refers to Don Quijote's discourse on arms and letters.) Then she accepted Marte's challenge and prepared for an Olympus showdown. Belona sided with Marte, while Apollo hopped to Minerva's side and stretched out his arrow ready for battle.

Seeing the warlike attitude of the gods, Jupiter's temper flared and he wielded his lightning. Like the wise Solomon he ended the debate by enlisting the help of a most impartial judge who will weigh (literally) the books in her scales using the highest standard possible (not the thickness, one presumes).

Mercurio put each of the two books (the Aeneid and the Quijote) first on the scales of Justice, and what do you know, the scales tipped right in the middle, not a hair's breadth more or less to the right or left! The two tomes were equal in weight. Mercurio removed the Aeneid and replaced it with the Iliad. Up and down went the two scales, up and down, the suspense built up. Then the two scales would stop at the very same level! Justice had spoken not in so many words. What Justice said, was justice served. Jupiter distributed the prizes to the three candidates.

JUPITER: [...] Mga diyoses at mga diyosas: Naniniwala ang KATARUNGAN na magkasimbigat ang tatlo: patas. Magsiyukod kayo, kung gayon at ibigay natin kay HOMERO ang trumpeta, kay VIRGILIO ang lira, at kay CERVANTES ang lawrel. Samantala, ilalathala ng FAMA sa buong daigdig ang pasiya ng KAPALARAN.

–

JÚPITER.

[...]

Dioses y diosas: la JUSTICIA los cree iguales; doblad, pues, la frente, y demos á HOMERO la trompa, á VIRGILIO la lira y á CERVANTES el lauro; mientras que la FAMA publicará por el mundo la sentencia del DESTINO.

Rizal's "Alegoría", as El consejo de los dioses was subtitled, unanimously won the first prize from the Liceo Artistico Literario de Manila. The play's epigraph "Con el recuerdo del pasado entro en el porvenir" (“I enter the future remembering the past”) hinted at the how the young Rizal valued and appreciated literature not only in literary terms but on "the weight of history", a world history fraught with monsters and wars, cruelties and inhumanities.

Unlike his two famous nationalist novels, Rizal's short play was often neglected because he wrote it when he was only a teenager. But here one could detect the source of didacticim in Philippine novel writing where writings were supposed to not only contribute to the development of literature but also to contribute to a positive change in attitudes and behaviors. The only possible arbiter of such writings is justice and to find justice in a work is to weigh them dispassionately and blindly. For Rizal, works that serve justice in all its forms are the kind of works that last, the works that must be celebrated are the ones that celebrate human dignity and human rights. Perhaps it is the "rights-based framework" of literary criticism that integrates the piecemeal concerns of Philippine literature. Not the Marxist alone, not the nationalist, not the feminist, not the queer, not the postcolonial.

*Above quotations in Filipino are from the translation of Virgilio S. Almario. The Spanish quotations are taken from El consejo de los dioses at Project Gutenberg which has slight variations from the Spanish in the book published by the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino.

02 December 2016

All books 2016

I read 42 books this year, lower than last year, which is lower than the year before that. This is the lowest since I started counting (and blogging) in 2009. The peak year is 2012 when I read 84 books.

Goodreads tells me I read 733 books in my lifetime so far, but this number is conservative. I could not account for all titles I read prior to 2009. I did not include in the catalog the books I read from the Hardy Boys series, Nancy Drew series, Hardy Boys Casefiles series, and Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys Supermystery series. Not to mention the Bobbsey Twins series and Tom Swift series. Not counting the children's picture books I pored over in the library. Funny graphic comics and other local comics being rented out by my grandmother in her sari-sari store. I am getting nostalgic.

Time is very forbidding, but I am happy to list whatever books I have the chance to read.

1. Contempt [post 1, post 2] by Alberto Moravia, tr. Angus Davidson

2. The Character of Rain [related post] by Amélie Nothomb, tr. Timothy Bent

3. Dr. Jekyll at G. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, tr. Largo Labor

4. Pitóng Gulod pa ang Layo at Iba pang Kuwento (Seven Hills Away and Other Stories) by N.V.M. Gonzalez, tr. Ed Maranan

5. The Golden Dagger by Antonio G. Sempio, tr. Soledad S. Reyes

6. Hinggil sa Konsepto ng Kasaysayan (On the Concept of History) by Walter Benjamin, tr. Ramon Guillermo

7. Bulosan: An Introduction With Selections by E. San Juan Jr.

8. Ang Maglaho sa Mundo: Mga Pilíng Tula (To Vanish from the Face of the Earth) by Jorge Luis Borges, tr. Kristian Sendon Cordero.

Also read and reviewed: Shakespeare's Memory, from Collected Fictions by Jorge Luis Borges, tr. Andrew Hurley

9. Bibliography of Filipino Novels: 1901-2000 by Patricia May B. Jurilla

10. Haring Lear by William Shakespeare, tr. and adapt. Nicolas B. Pichay

11. Konseho ng mga Diyoses Sa May Ilog Pasig (Council of the Gods by the Pasig River) by José Rizal, tr. Virgilio S. Almario and Michael M. Coroza

12. The Monkey and the Tortoise: A Tagalog Tale by José Rizal, illus. Bryan Anthony Paraiso

13. The Bamboo Stalk by Saud Alsanousi, tr. Jonathan Wright

14. Shri-Bishaya [post 1, post 2] by Ramon Muzones, tr. Ma. Cecilia Locsin-Nava

15. Juanita Cruz by Magdalena Gonzaga Jalandoni, tr. Ofelia Ledesma Jalandoni

16. A Lion in the House by Lina Espina-Moore

17. Typewriter Altar by Luna Sicat Cleto, tr. Marne L. Kilates

18. A Place in the Country by W. G. Sebald, tr. Jo Catling

19. Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change by Elizabeth Kolbert

20. Halina Filipina by Arnold Arre

21. House of Cards by Austregelina Espina-Moore, tr. Hope Sabanpan-Yu

22. Diin May Punoan sa Arbol (Where a Fire Tree Grows) by Austregelina Espina-Moore, tr. Hope Sabanpan-Yu

23. Ang Inahan ni Mila (Mila's Mother) by Austregelina Espina-Moore, tr. Hope Sabanpan-Yu

24. Martial Law Babies by Arnold Arre

25. Zsazsa Zaturnnah sa Kalakhang Maynila (Part Two) by Carlo Vergara

26. Love in the Rice Fields and Other Short Stories by Macario Pineda, tr. Soledad S. Reyes

27. Pag-aabang sa Kundiman: Isang Tulambúhay (Waiting Along Kundiman: Autopoetry) by Edgar Calabia Samar

28. At the Same Time: Essays and Speeches by Susan Sontag, ed. Paolo Dilonardo and Anne Jump

29. 84, Charing Cross Road by Helene Hanff

30. Ilustrado by Miguel Syjuco

31. Testment and Other Stories by Katrina Tuvera

32. A Blade of Fern by Edith L. Tiempo

33. At the Mind's Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor of Auschwitz and Its Realities by Jean Améry, tr. Sidney Rosenfeld and Stella P. Rosenfeld

34. Encyclical on Climate Change and Inequality: On Care for Our Common Home by Pope Francis

35. The Metamorphosis, In the Penal Colony, and Other Stories by Franz Kafka, tr. Joachim Neugroschel

36. A Roomful of Machines by Kristine Ong Muslim

37. The Pact of Biyak-na-Bato and Ninay by Pedro A. Paterno, tr. National Historical Institute and E. F. du Fresne

38. The Birthing of Hannibal Valdez by Alfrredo Navarro Salanga, with an accompanying Pilipino translation by Romulo A. Sandoval

39. The Alien Corn by Edith L. Tiempo

40. Stringing the Past: An archaeological understanding of early Southeast Asian glass bead trade by Jun G. Cayron

41. The True Deceiver by Tove Jansson, tr. Thomas Teal

42. Ang Balabal ng Diyos / Ang Silid ng Makasalanan (The Cloak of God / The Sinner's Room) by Rosario de Guzman Lingat [review of the English translation The Cloak of God here]